Why You Should Overdeliver

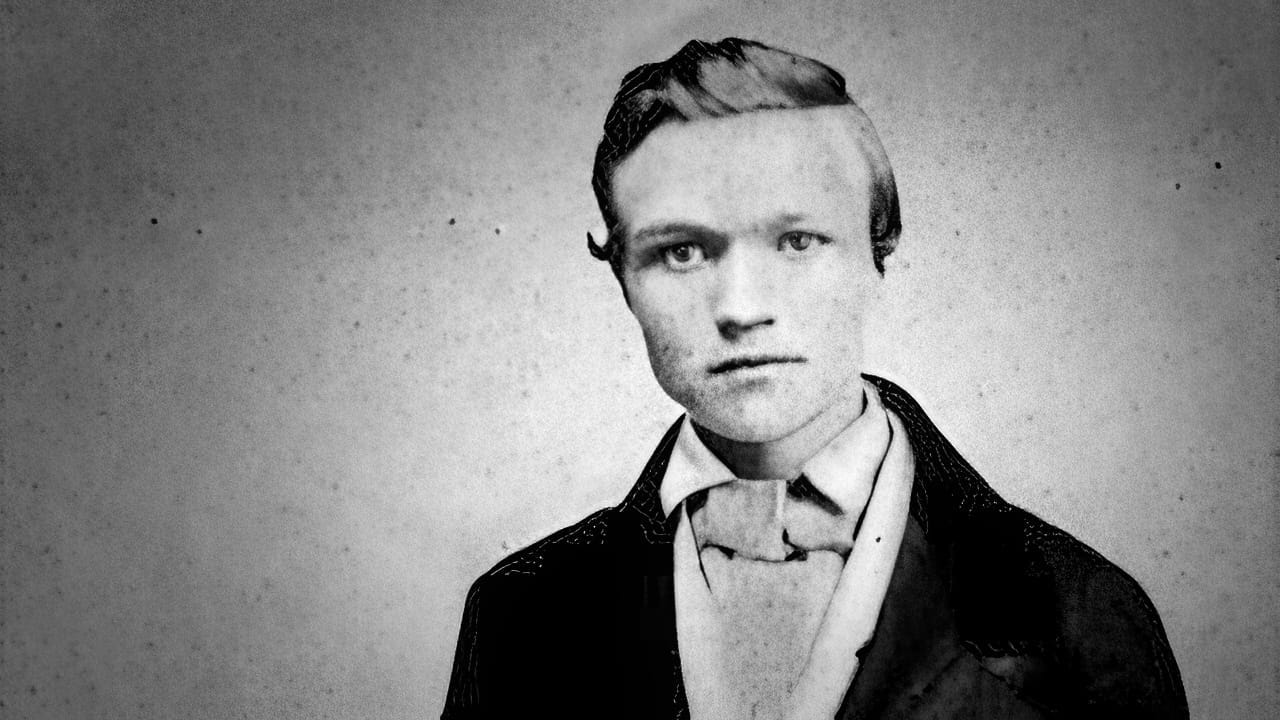

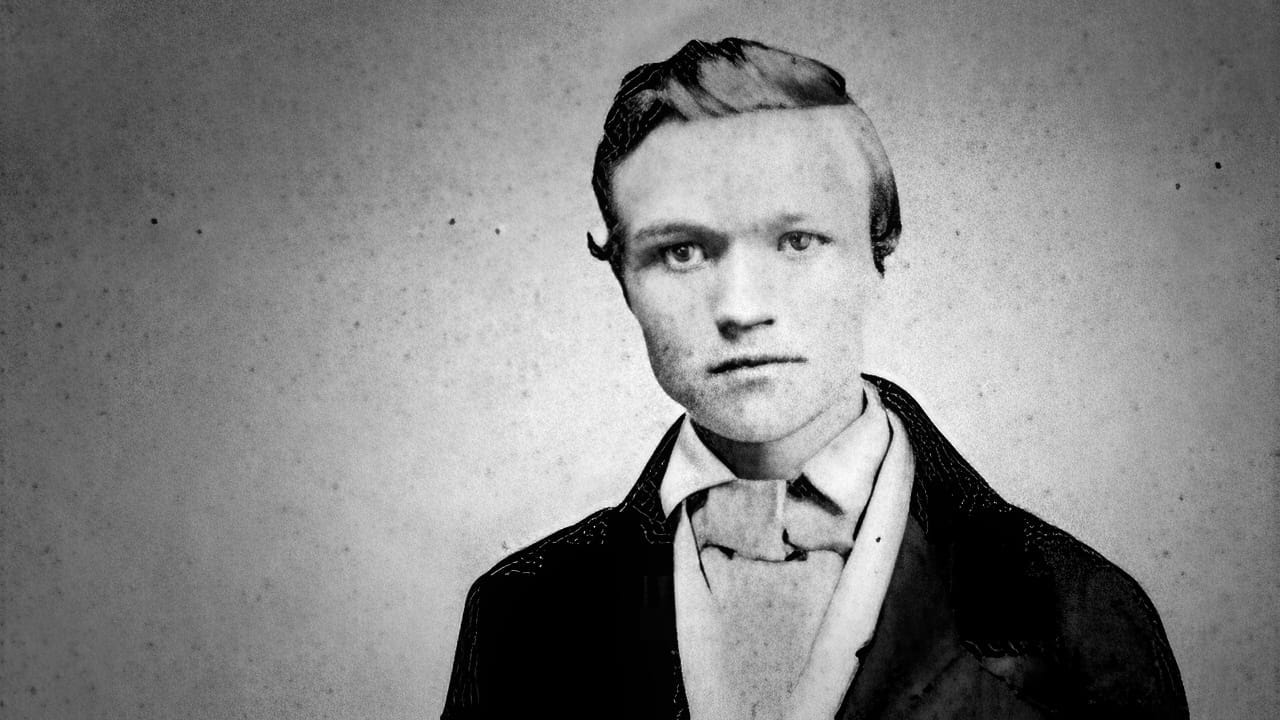

Andrew Carnegie's rise out of poverty

We live in an age of complacency: screens seduce us into endless scrolling, delivering constant dopamine hits and distraction; food shows up at the door with simply a tap of the finger; and now ChatGPT gives us all the answers.

Sure, things have escalated — but the urge to conserve energy is nothing new. Back in the 1800s, humanity’s tendency toward idleness was realized by a gifted young boy who tried desperately to improve his lot in life.

Andrew Carnegie discovered early on that in others' complacency lies opportunity. And he seized it.

Throughout Carnegie's life, there’s one principle he applied over and over again to give him an edge...

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Beginning

The year was 1850, and Pittsburgh hummed with the energy of America's industrial revolution. Smokestacks belched coal soot into the air as factories, railroads, and a new invention called the telegraph were transforming the nation.

Among the crowds navigating these sooty streets was a 15-year-old boy named Andrew Carnegie, whose chance encounter at a telegraph office would lift the uncertainty surrounding his path to success and teach him how to ascend in the world.

The son of a Scottish immigrant family struggling to make ends meet in America, Carnegie carried the weight of his family's financial survival on his young shoulders. Have you ever seen those famous photos from the 1800s of the dirty, ragged looking boys in the streets? Well, Carnegie was one of the boys…

His family had fled crushing poverty in Dunfermline when mechanized looms destroyed his father's livelihood as a handloom weaver. His mother bound shoes by candlelight, often working past midnight to earn four dollars a week. His father then took whatever work he could find, making tablecloths and other odd jobs. The only hope for young Andrew’s future lay in his own hands.

The Telegraph Office

For young Andrew, life was a constant scramble. He had already worked in a cotton factory as a bobbin boy for $1.20 a week, and now served as a messenger for a telegraph office for slightly better pay. At the office before anyone else, his first duty was to sweep the operating room before the telegraphers arrived. But while Carnegie swept in the cold, dark offices, his curiosity grew. Eventually one day after finishing his sweeping, he quietly approached the mysterious telegraph machines. These technological marvels could instantly transmit messages across vast distances—a revolutionary advancement in communication.

Though no one had instructed him to do so, Andrew taught himself how the instruments worked. "I soon began to play with the key and to talk with the boys who were at other stations who had purposes similar to my own," he later wrote. Every spare moment became an opportunity to practice, learning the patterns and rhythms of Morse code through sheer focus and persistence. (We will return to Carnegie’s focusing abilities in a future article. It’s well worth studying).

This self-directed learning wasn't part of his job description, as you might imagine. As a messenger boy earning modest wages, no one expected him to master the telegraph. Yet Andrew understood something fundamental:

"Whenever one learns to do anything, he has never to wait long for an opportunity of putting his knowledge to use."

The Opportunity

That opportunity arrived unexpectedly one morning when an urgent message came through from Philadelphia while no operators were present. Though unauthorized to do so, Andrew made a decision. He sat down anxiously at the telegraph key and responded, explaining he was only a messenger but would try to receive the message if they sent it slowly.

Concentrating intensely, he successfully transcribed the urgent death notification and immediately delivered it to the intended recipient. When his supervisor, Mr. Brooks, arrived, Andrew confessed his unauthorized actions. Rather than being reprimanded, his initiative was recognized and rewarded with temporary telegraph duties during operators' absences.

His opportunity expanded when Mr. Brooks asked if he could fill in for an operator in Greensburg, PA who needed two weeks off. Without hesitation, Andrew accepted. For a boy who had never traveled beyond Pittsburgh, this was an adventure into the unknown.

However, Andrew faced some challenges while in Greensburg. One was especially shocking: One night, Carnegie got caught in a lightning storm while working the telegraph key. He recalls the event as an old man:

“I was so anxious to be at hand in case I should be needed, that one night very late I sat in the office during a storm, not wishing to cut off the connection. I ventured too near the key and for my boldness was knocked off my stool. A flash of lightning very nearly ended my career.”

How many telegraph officers had that kind of commitment?

Upon his return, Andrew's reputation had grown. Shortly after, he received a promotion to assistant operator with a salary of twenty-five dollars a month — a sum he considered "a fortune." These early triumphs were revelatory to Carnegie. He recalls his first promotion and his parents’ reaction: "Father's glance of loving pride and mother's blazing eyes, soon wet with tears, told their feeling," he recalled. "No subsequent success or recognition of any kind ever thrilled me as this did."

It’s at this point that Carnegie begins to see a truly bright future for himself and his family, as he shares in his autobiography:

"Tom, a little boy of nine, and myself slept in the attic together, and after we were safely in bed I whispered the secret to my dear little brother. Even at his early age he knew what it meant, and we talked over the future. It was then, for the first time, I sketched to him how we would go into business together; that the firm of "Carnegie Brothers" would be a great one, and that father and mother should yet ride in their carriage."

The American dream in the hearts of two young children. Quite the scene.

The Ascension Begins

His telegraph skills soon caught the attention of Thomas Scott, superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad's Western Division. Scott offered Andrew a position as his personal clerk and telegraph operator at thirty-five dollars a month. This placed the young man at the intersection of America's two most dynamic technologies — railroads and telegraphs.

This was just the beginning of a path that would eventually lead him to become one of the wealthiest men in the world through his steel empire. But it all started with a broom, a telegraph key, and a boy who recognized the value of seizing the opportunities that presented themselves.

Years later, reflecting on his rise from messenger boy to industrial titan, Carnegie wrote:

"Experience tends to confirm a long-held notion that being prepared, on a few occasions in a lifetime, to act promptly in scale, in doing some simple and logical thing, will often dramatically improve the financial results of that lifetime."

The telegraph skills he taught himself when no one was watching opened doors that would have remained closed to the son of a poor immigrant. By making the most of the opportunity directly in front of him — even when it was just sweeping floors — Andrew Carnegie built the foundation for extraordinary achievement.

I think whilst he had a certain get up and go mentality that fits with American capitalism and can be seen as optimistic. I think here in Europe we see it as hustle culture and would rather use our energy to organise unions, strikes or protests etc. I’m from Nottingham, UK so Robin Hood is my muse :)

I would like to read a biography of Andrew Carnegie. Does anyone have a good one to recommend?