Why Romans Guarded Religion

The civic function of ritual....

The modern age is plagued by spiritual uncertainty and an erosion of shared values — just like the Romans nearly two millennia ago. However, by reaching back to the Roman concept of religio, we can better understand the roots of our own societal malaise.

To the Romans, religio was far more than a matter of private belief or personal devotion, it was a binding force that united individuals within a framework of collective ritual, tradition, and civic responsibility, one of the integral pillars of the Mos Maiorum, the “way of the ancients”.

The Roman experience reveals how the dissolution of a common religious fabric can precipitate moral decline, social fragmentation, and, ultimately, the weakening of civilization itself.

But none of this took the Romans by surprise – they long understood the importance of a common religious experience and guarded it carefully.

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

A Communal Affair

In Ancient Rome, religio was the foundation of civic life and the greatest expression of the Mos Maiorum.

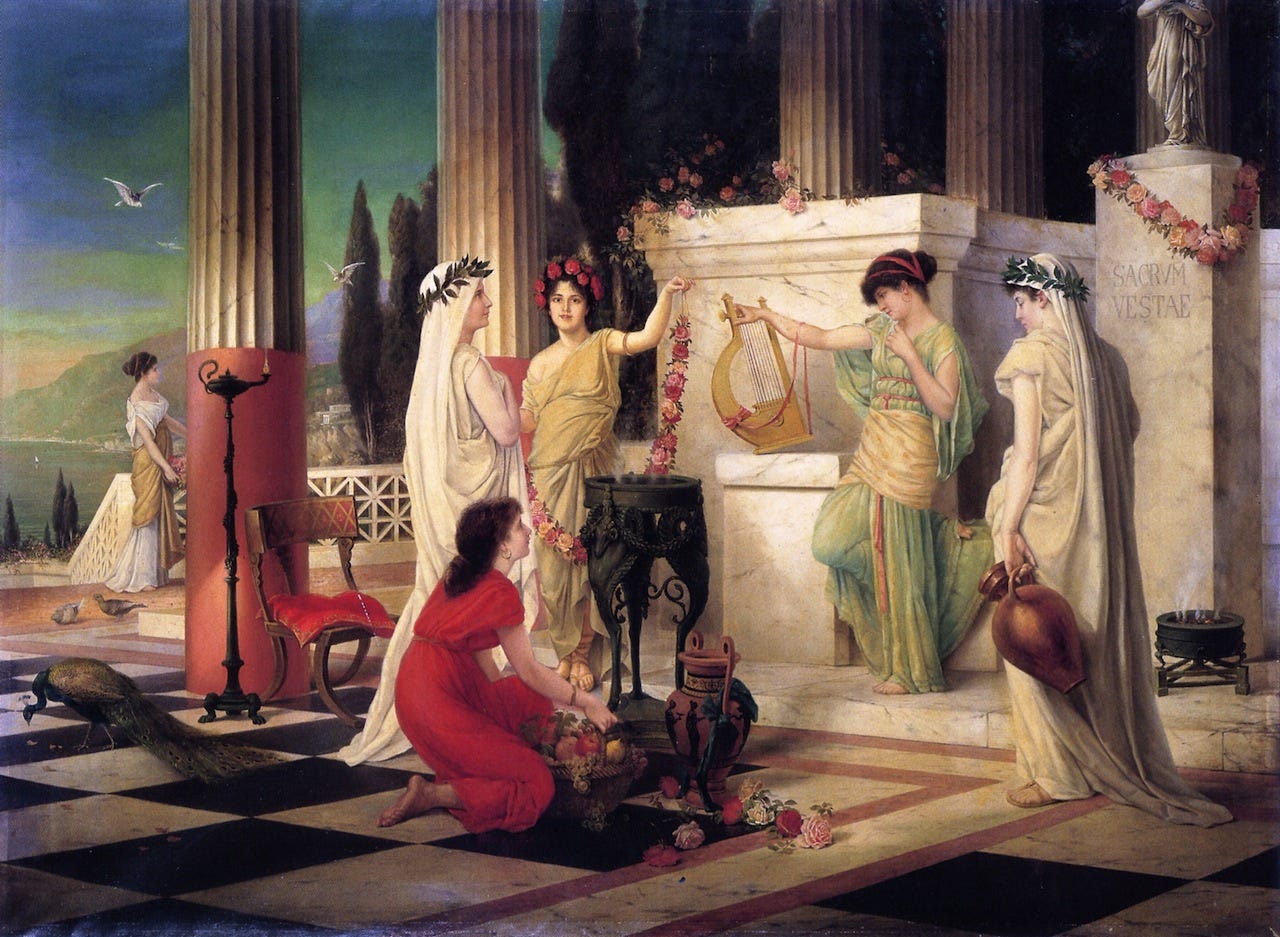

According to the Romans, religio was embodied in the proper, communal performance of state‐sanctioned rituals, prayers, and sacrifices. These were a constellation of practices meticulously governed by tradition and under the watchful eye of the state.

At the heart of the Roman system of religion laid the principle of do ut des (I give, that you might give), which established and maintained a reciprocal relationship between the Roman people and the gods.

In exchange for their diligent observances, the Romans believed that the gods would continue to grant them favor and protection. Participation in these elaborate rites and rituals was not considered a reflection of one’s personal devoutness but a public affirmation of the values that united all Romans.

The very structure of the Roman calendar — punctuated by numerous religious observances — ensured that every citizen, noble or slave, man or woman, was continuously reminded of and bound to the sacred duties of civic life.

Roman intellectuals and statesmen repeatedly emphasized that religio was inseparable from the well-being of the state.

The great Roman statesman and orator, Marcus Tullius Cicero, served as an augur and insisted that religio – more specifically, pietas (piety) — was far more than a private sentiment, but a civic obligation on which the strength of the state depended.

In his De Natura Deorum, he argued that the Romans’ strict observance of religio was the foundation of their empire’s success.

"For not only individuals, but even whole peoples, often perish through a certain obstinacy and perverseness in neglecting the worship of the immortal gods... We have excelled all nations and peoples in piety and in religion, and by this we have gained dominion over the world”.

As he conveyed the essential link between ritual and the common good, one is reminded that for the Romans the collective duty to maintain the Mos Maiorum by honoring the gods according to their ancestral rites was a bulwark against chaos and civilizational degeneration.

Public Over Personal

Yet there was a striking duality in Roman attitudes toward personal faith and spirituality. While public ritual was sacrosanct, Romans remained deeply suspicious of private, individual religious experiences.

Faith, they believed, was meant to be expressed collectively, not as a solitary or inner emotion, and any deviation from established practice — whether through neglect, excessive innovation, or unorthodox individual expression — was perceived as a threat to and violation of the Pax Deorum (peace of the gods).

Public rites, performed openly by state-appointed priests, reinforced civic duty and community loyalty; in contrast, private or ecstatic forms of worship were dismissed as superstitio, dangerous religious anomalies that disrupted social stability and were liable to provoke divine vengeance upon the Roman people.

In this context, jus divinum (religious law) was dedicated almost exclusively to the maintaining correct performance of religious acts, the prohibition of innovation, and relegating personal spirituality to a secondary plane in favor of collective identity.

Threats to Unity

Eastern mystery cults, most notably those associated with the Bacchanalia and the cult of Isis, were understood as threats to the empire. Livy’s account of the Bacchanalia scandal is particularly vivid: he describes the cult’s frenzied rites, marked by sexually violent initiations and a blatant disregard for long-established customs.

According to his narrative, these rites seduced the most vulnerable sectors of society — from young citizens and plebeians to women — thereby eroding traditional Roman values and imperiling the state’s future. The Senate’s dramatic interventions through mass arrests and severe punishments were seen as a necessary measure to prevent the disintegration of Rome’s collective moral fabric.

The great Roman historian Livy captures this sentiment in no uncertain terms. Like many Romans of his time, Livy believed that the introduction of Eastern mystery cults, which relied on private supernatural experiences, weakened religio specifically and the Roman people in general.

In his Ab Urbe Condita, Livy reflected on the current crisis, stating

“Under the guise of religion, priests and acolytes broke civil, moral and religious laws with impunity; weak-minded individuals could be persuaded to commit ritual or political murders undetected, at the behest of those who secretly controlled the cult, right in the heart of Rome.

"There was nothing wicked, nothing flagitious, that had not been practised among them. More crimes were committed by men with each other than with women. If any were less patient in submitting to dishonour, or more averse to crime, they were offered up as victims. To regard nothing as unlawful was the very sum of their religion."

He then declared,

“The cause of our misfortune is the neglect of the gods; let us return to the temples, let us renew the ancient rites”.

Like many Romans, Livy recognised that Roman religio was the foundation of the Mos Maiorum. His warning that the widespread introduction of foreign religions that were incompatible with Roman values would inevitably lead to the destruction of the family, the dissolution of civil loyalty, the fragmentation of social cohesion and the eventual collapse of the empire came to fruition.

A Common Identity

Roman religio was not simply a personal quest for divine favor; it was a public duty that undergirded the legal, political, and social order of Rome. Through its rigorous observance, the ancient Romans wove together their family, military, and civic institutions into a resilient tapestry of common identity.

Their steadfast commitment to tradition ensured that every ritual performed was, in essence, an affirmation of a shared legacy — one that sustained Rome’s greatness through law, order, and community.

The Romans recognized that allowing foreign mystery cults and religions fundamentally incompatible with their own traditions would not merely undermine the moral integrity of their citizens, but also sow internal discord. They knew that such divisions would rupture the Pax Deorum and ultimately lead to the collapse of their empire as a result of divine retribution.

History doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme…

How Rome forced religion on its citizens and stifled dissent and individual worship to maintain an empire—no thanks. This is subverting our connection to the Divine.

No pope and no king in America.