Where Great Art Truly Begins

How Classical Draftsmanship Built the Foundations of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture

The Sistine Chapel ceiling, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, and the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore all share a common golden thread. Each of these iconic achievements began the same way: with a line drawn on paper.

In the world of classical art, drawing wasn’t just preparation. It was creation. Whether designing temples, sculpting gods from marble, or painting myth onto plaster, the artist began with a sketch — for the purpose of defining its structure.

Drawing was the keynote behind all visual disciplines, the geometry beneath beauty, the thread that stitched vision to form. In the classical tradition, drawing was art — a universal language of design, proportion, and clarity.

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Drawing as Discipline

In modern education, we often see drawing as a skill for illustrators, hobbyists, or maybe the first phase of a painting. But to the Renaissance master, it was the most rigorous of disciplines.

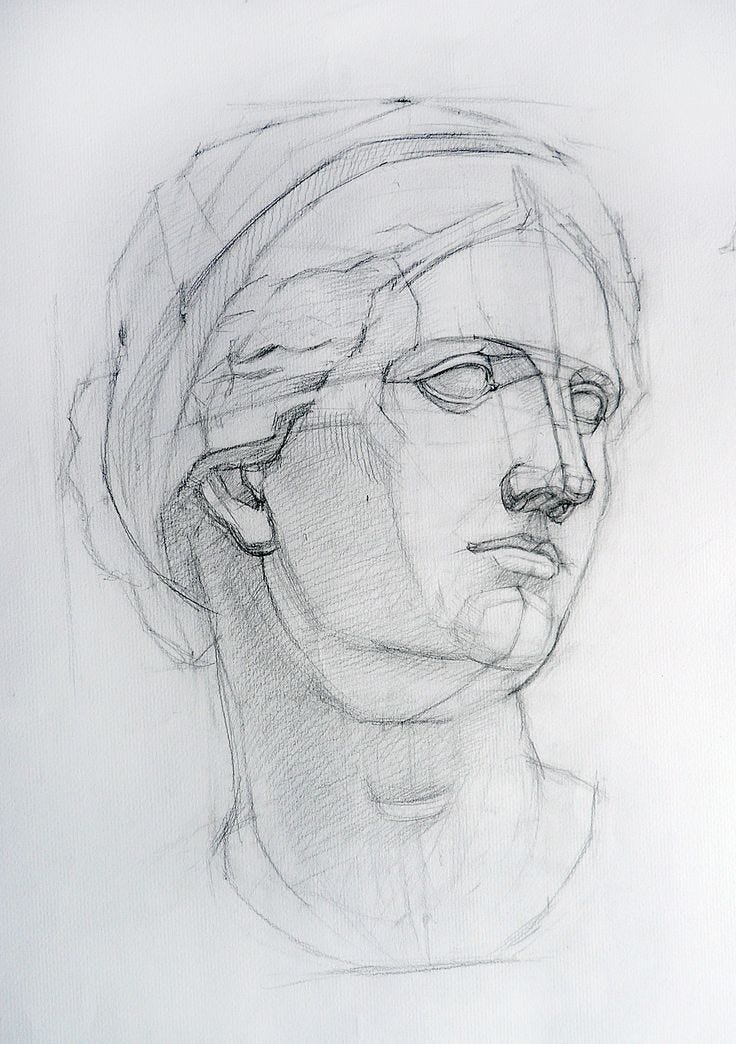

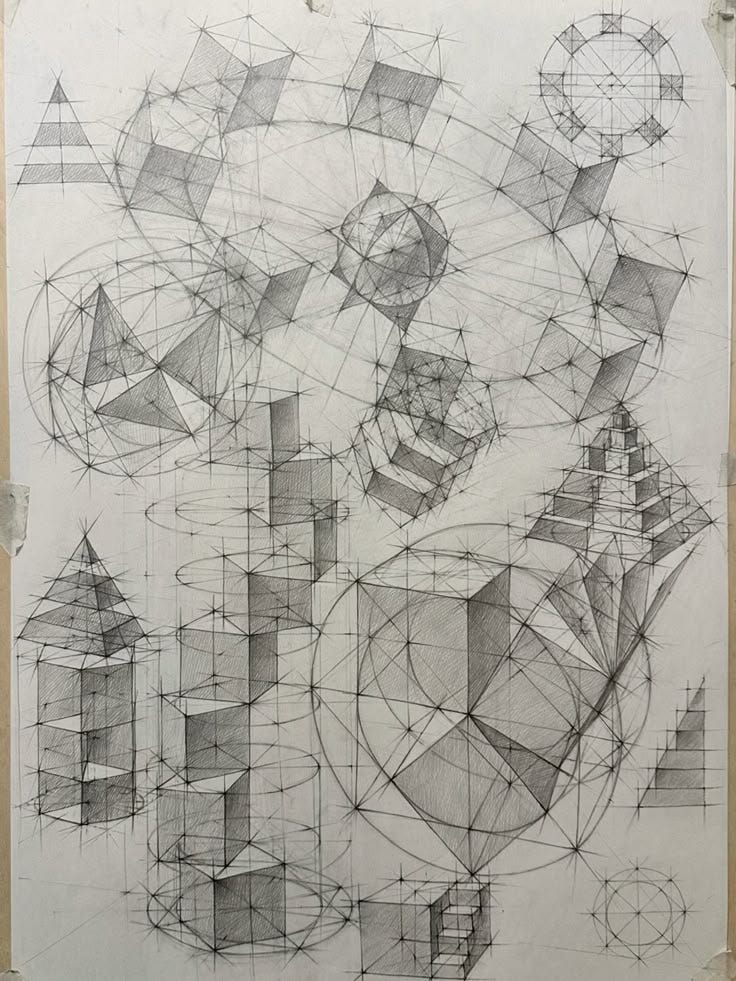

Classical drawing demanded knowledge of anatomy, optics, geometry, and light. Students didn’t just draw what they saw — they learned to see through structure. They studied how muscle followed bone, how shadows turned across planes, how light curved around a sphere. Every line on paper represented a decision — measured, intentional, and rooted in nature’s logic.

Drawing was a way of thinking, a way of knowing.

The Idea That Changed Everything

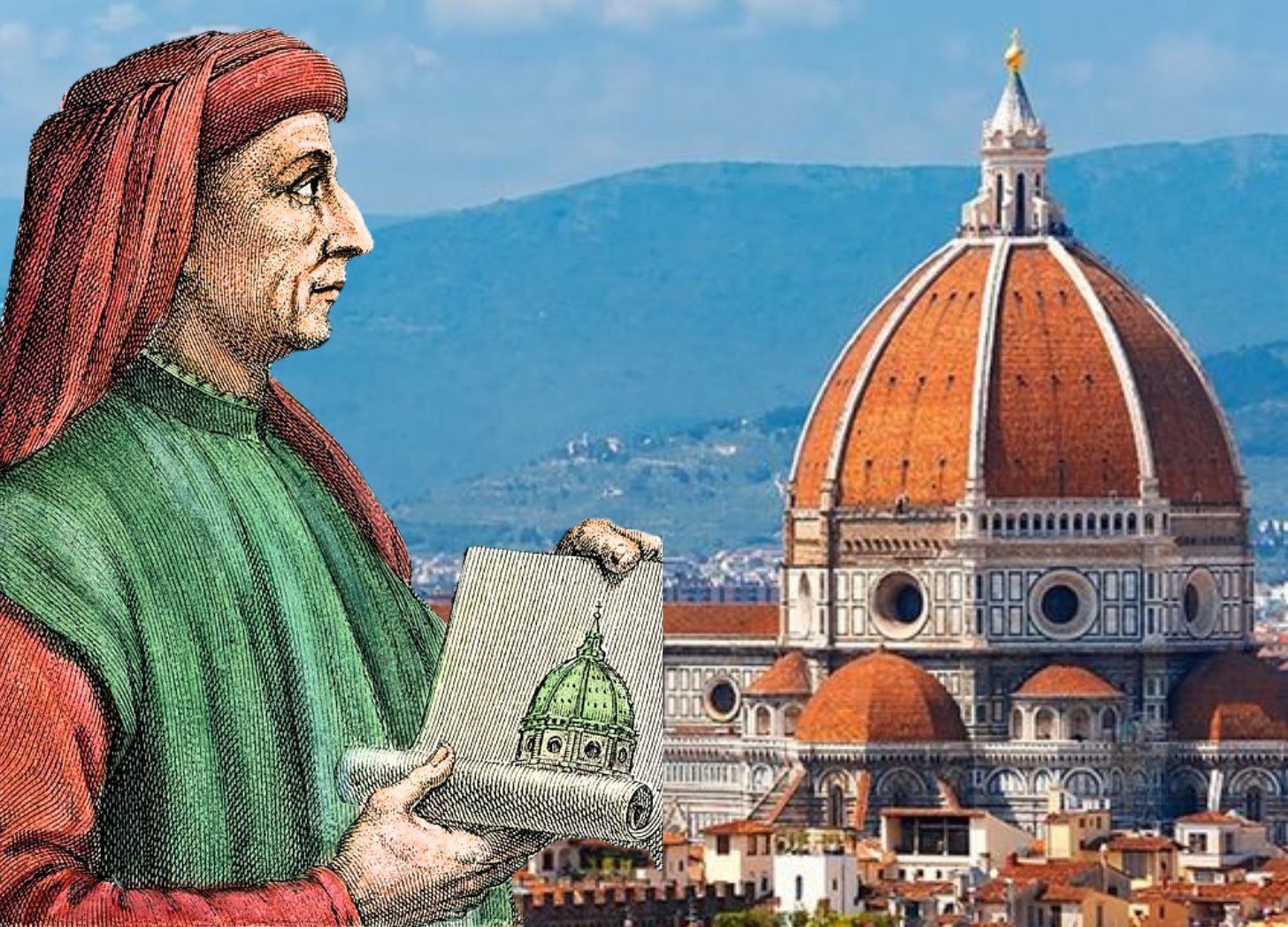

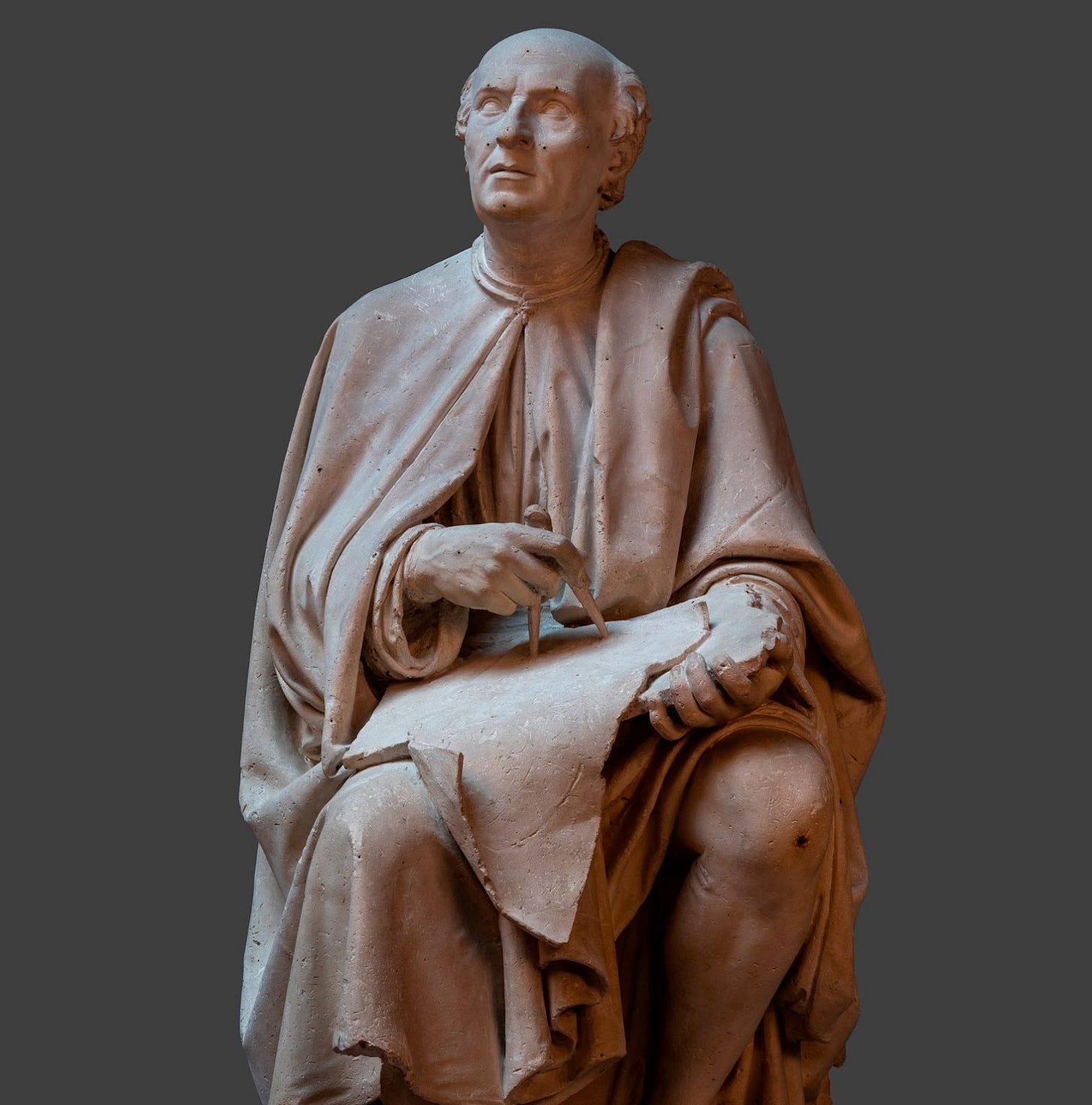

Filippo Brunelleschi is remembered today as the architect of Florence’s massive cathedral dome. But his greatest artistic legacy is largely overlooked: he was the first to codify linear perspective.

What is linear perspective?

It’s a technique used in art to create the illusion of depth and three-dimensionality on a flat surface.

With a mirror, a panel, and a vanishing point, Brunelleschi proved that spatial depth could be measured and plotted. He showed that the receding lines of a street or a tiled floor obeyed a geometric logic. With this discovery, the Renaissance vision was born: art that mimicked not just what the eye saw, but how space itself was ‘structured.’

Painters and artists everywhere quickly adopted the technique.

The Shared Geometry of the Visual Arts

We often separate art into distinct fields: painting, architecture, sculpture, etc. But in the classical era, all three grew from a common root: drawing. Artists across disciplines used the same visual grammar:

Horizon lines

Vanishing points

Orthogonals

Golden sections

Geometric divisions

Whether plotting a building elevation or designing a fresco, the artist began with these same tools. They now had a system to bring the order of heaven to the canvas — harmonizing form, function, and emotion. They were all composing their artistic symphonies — on paper first using linear perspective.

Raphael: Heart of a Painter with a Mind of an Architect

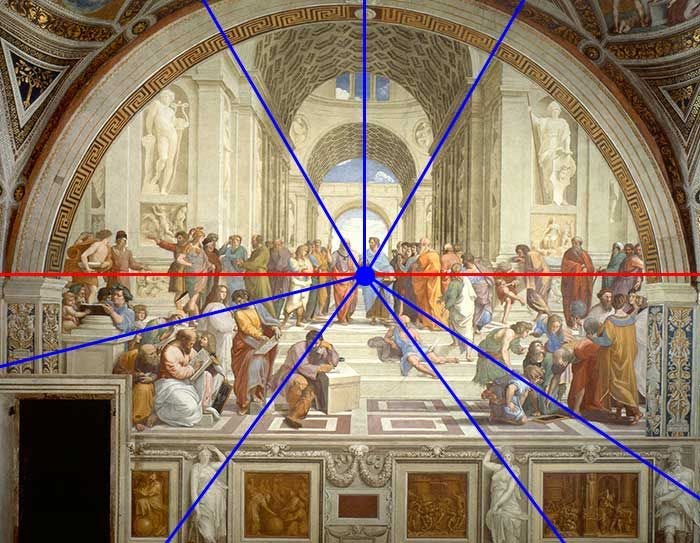

No one exemplified this unity more than Raphael. Look closely at The School of Athens. It’s not just a painting of the greatest western figures — it’s in a temple. Every arch, every column, every coffered ceiling is drawn with architectural precision.

Before he added philosophers, Raphael mapped the entire composition using drawing techniques found in Vitruvian plans and perspective treatises. The composition is composed in one point perspective with the main vanishing point between Plato and Aristotle — a masterclass in the use of linear perspective.

Michelangelo: Sculptor of Shadow

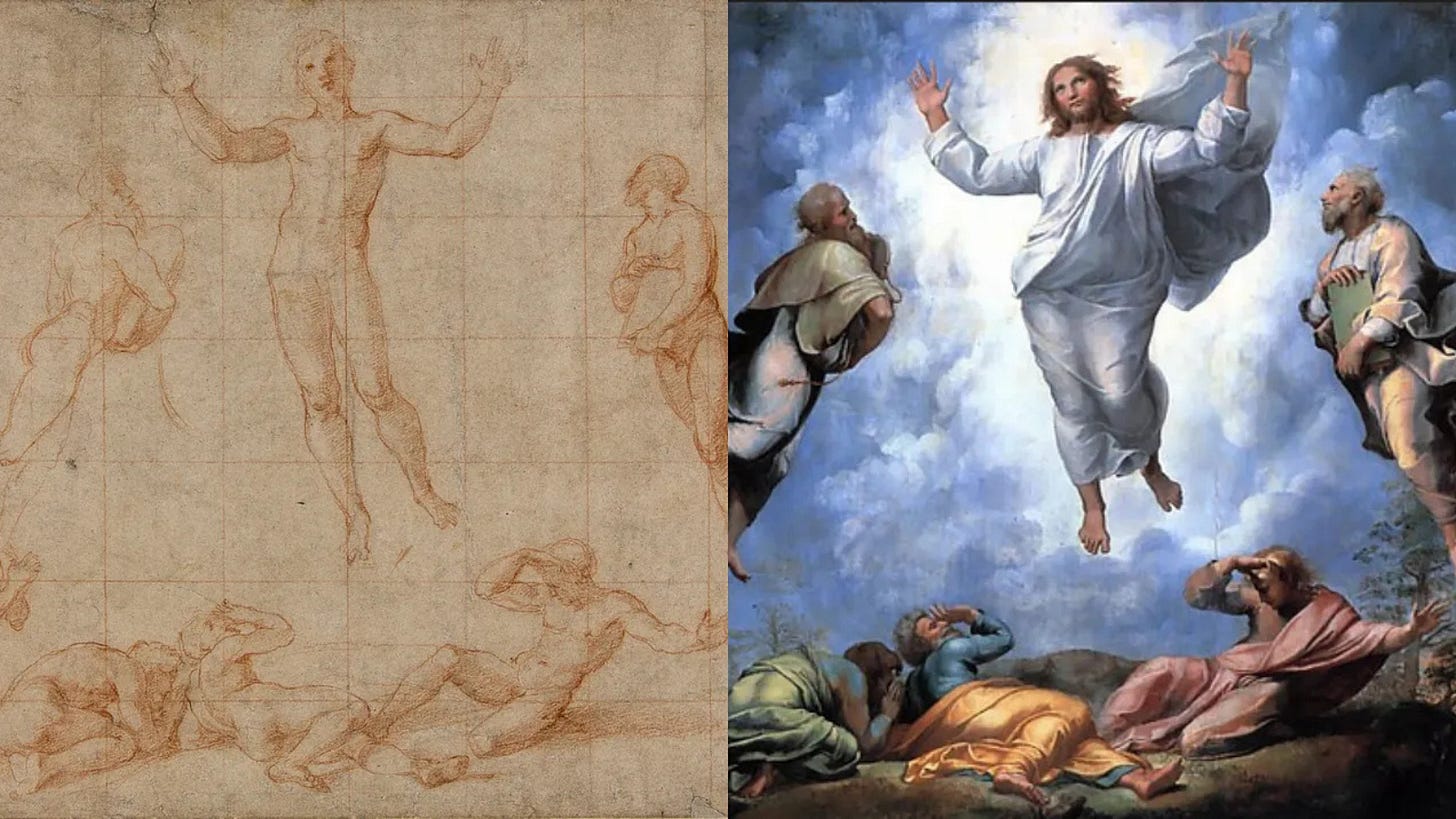

Even Michelangelo, the titan of marble, began with the pencil. His red chalk studies are legendary. Muscles twist, stretch, and coil across the page — not as outlines, but as volumes shaped and divided by shadow.

Through chiaroscuro — the use of light and dark to model form — Michelangelo sculpted with pencil what he’d later carve in stone or paint on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Drawing was how he tested weight, gesture, and anatomy.

Michelangelo so strongly believed in the importance of drawing that he once told his student Antonio Mini:

"Draw Antonio, draw Antonio, draw and don't waste time."

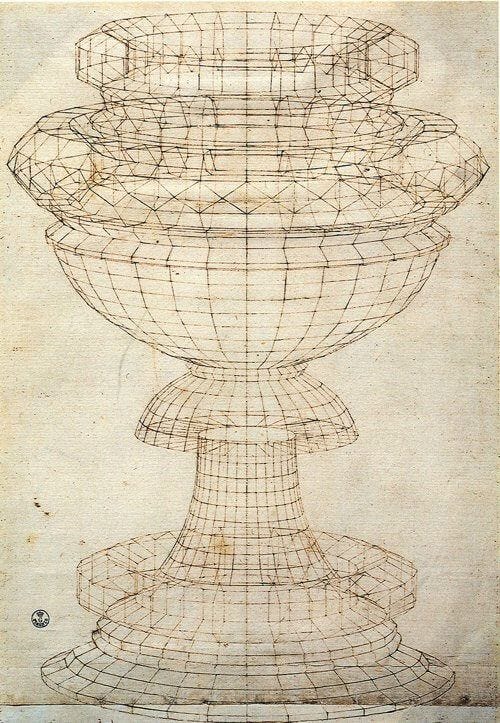

The Ideal City Was Drawn

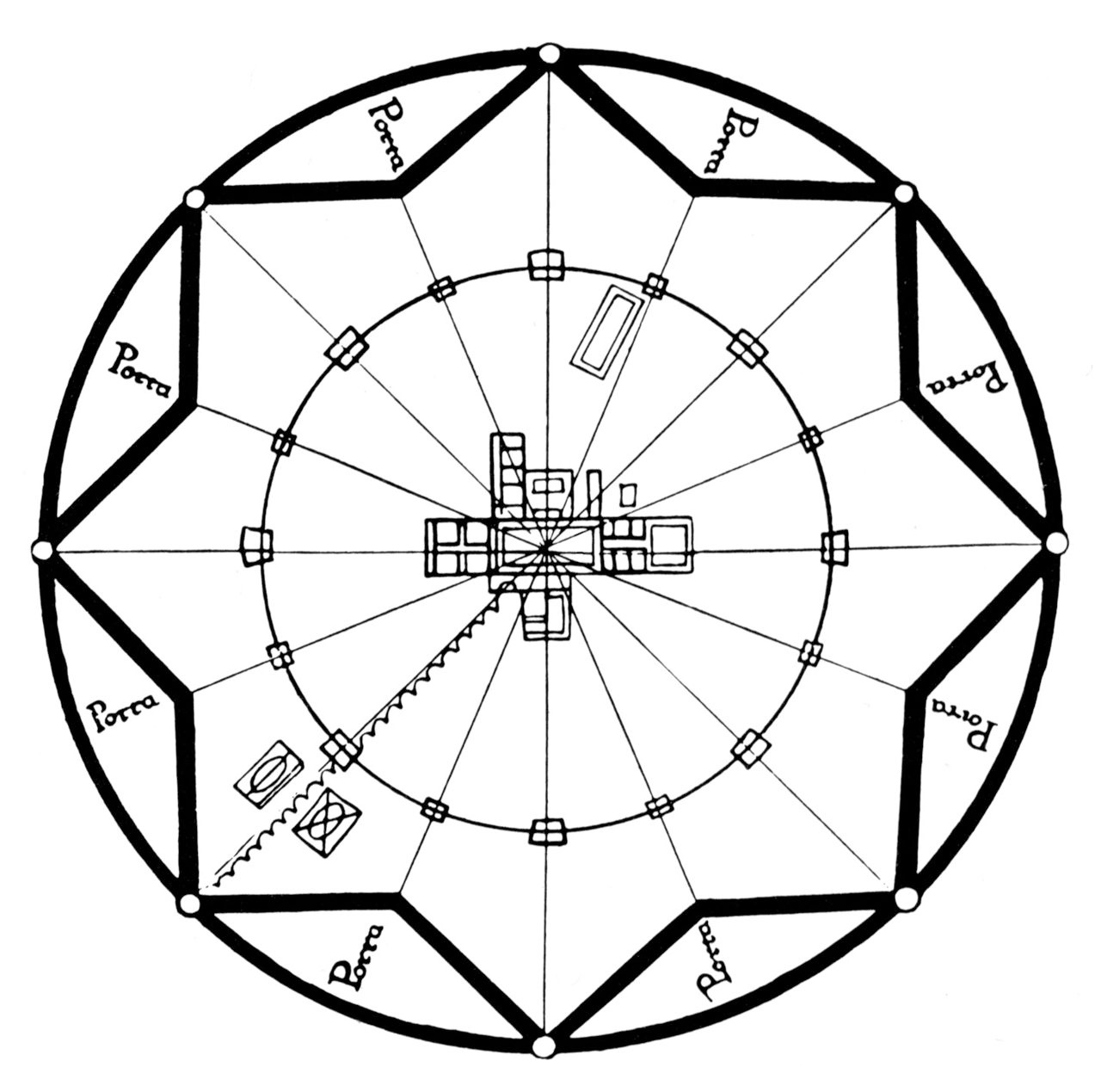

It wasn’t only figures and buildings that began as drawings — entire cities were conceived with a pencil. Renaissance architects like Leon Battista Alberti and Antonio Filarete imagined “ideal cities” laid out using geometric grids, golden ratios, and radial symmetry.

These designs were never arbitrary. They followed the same geometric logic found in the human body, the Vitruvian Man, and the Parthenon.

The 5:8 (Fibonacci numbers approximating the golden ratio) defined plaza widths

Street grids radiated from centralized points.

Building facades echoed musical intervals.

Urban beauty was a drawn equation as seen in Filarete’s ideal city of Sforzinda below.

Drawing Light: From Paper to Architecture

Light is central to all visual art. But long before electric lighting plans, artists mastered how to draw light. In classical drawing, light and shadow gave form its depth. The same techniques used in drawings of spheres, cubes and figures shaped how architects thought about space and the forms which occupy it.

Oculi at the top of domes, rose windows, recessed chapels — all were designed with the movement of light in mind — especially linked to solstices and equinoxes. The eye that could draw a cast shadow on a cube could also design a cathedral that captured sunrise.

Let There Be Light

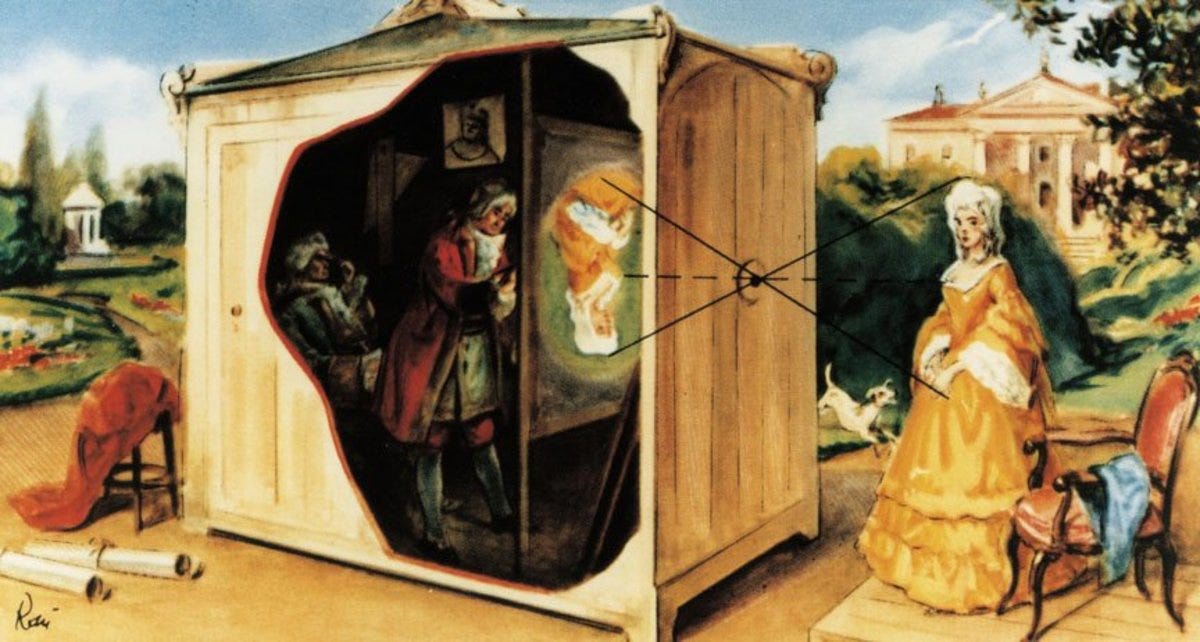

Drawing also gave rise to early experiments in optics. The camera obscura — a darkened box with a small aperture — projected scenes onto walls or paper. Artists used it to trace accurate images.

But architects studied it to understand how light entered a room. It influenced window placement, interior design, and even celestial alignment in sacred spaces.

Once again, a tool of drawing became a tool of design. The hand followed the light.

Why It All Comes Back to the Line

As you can see from this article, the classical masters didn’t see drawing as an afterthought. They saw it as the origin.

Painting is drawing in color. Sculpture is drawing in three dimensions. Architecture is drawing made habitable.

Every major work of Western art — from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel to the dome of St. Peter’s — emerged from a line first sketched by hand. Drawing was never optional. It was the original creative act.

Conclusion: Drawing Is the Architecture of Thought

In a time before Photoshop or CAD, the pencil, compass, and straightedge reigned. In the old days, drawing wasn’t only a technique — it was a philosophy. It unified the visual world, taught artists how to think, and made the invisible, visible.

Next time you look at a great painting, walk through a beautiful plaza, or stand beneath a stone arch, remember: It all began with the simplest of acts — a line.