The Source of Roman Exceptionalism

Mos Maiorum and Romanitas

How did a humble settlement on the banks of the Tiber rise to become the greatest empire in Western history? Was it chance, fortune, geography – or something more profound?

In order to understand Roman civilization, one must look beyond its political institutions and military conquests to the ideals that forged Roman identity, setting these conquerors apart from those they conquered. At the heart of this identity stood two guiding principles – the Mos Maiorum and Romanitas. Together, these ideals illuminate the Roman worldview and reveal how the Romans conceived of themselves as a civilisation destined for greatness.

Mos Maiorum: The Way of the Ancestors

The Mos Maiorum or “way of the ancestors” were the unwritten traditions and practices handed down from Rome’s forefathers from its foundation. Although these were not codified in law, the Mos Maiorum represented the accumulated wisdom of past generations, and as a result, were considered binding on the present.

At the centre of the Mos Maiorum was the Via Romana or “the Roman Way” – the virtues that every Roman man and woman was expected to exemplify. A senator was expected to uphold dignitas in preserving the honor and prestige of his office, to demonstrate fides in remaining loyal to his allies and obligations, and to exercise prudentia in guiding the affairs of state with wisdom and foresight. Similarly, a centurion was expected to uphold disciplina in drilling his legionaries, to display fortitudo in the face of danger, and to exercise auctoritas in commanding respect through the strength of his character. Finally, a matriarch was expected to embody pietas in her devotion to the household gods and family, to display frugalitas in managing the resources of the home with prudence, and to uphold dignitas by maintaining the honor and reputation of her lineage.

The Mos Maiorum was also evident in Roman religion and politics. Elaborate religious rituals were carefully crafted over centuries with rubrics meticulously observed as they were believed to have been instituted by the ancestors. Similarly, political institutions such as the Senate derived their authority from their continuity with tradition effectively blurring the lines between the sacred and the secular. Echoing the sentiments of his Roman contemporaries, Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote in his De Legibus that “Many things were admirably established by our ancestors and ought to be preserved by us as sacred”. He believed that the Mos Mairoum served as a safeguard against novelty and innovation, and to deviate was to undermine the very foundations upon which Roman Civilization was built.

Romanitas: What it Means to be Roman

The term Romanitas was not one the Romans themselves commonly used, but later historians have adopted to describe the values, practices, and attitudes that Romans believed distinguished them from other peoples. Popularized in the 3rd century by the Christian apologist Tertullian, Romanitas referred to “Romanness” or the constellation of cultural values, political ideals, and social practices that defined what it meant to be a Roman.

Unlike other ancient powers, Rome did not merely subjugate conquered peoples but it sought to integrate them into its civic framework by extending citizenship and legal rights in a gradual but deliberate manner. This inculturation, though hierarchical, was a hallmark of Roman identity and is what drove many former barbarians into the Roman fold. Such a policy was not only pragmatic but also ideological as it reinforced the notion that Roman identity was expansive and capable of absorbing diverse peoples into the orbit of Romanitas – but this process was always approached with proportionality and moderation.

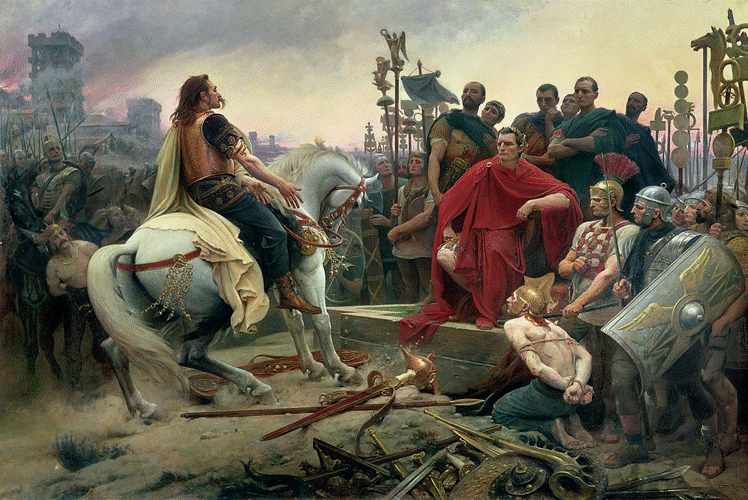

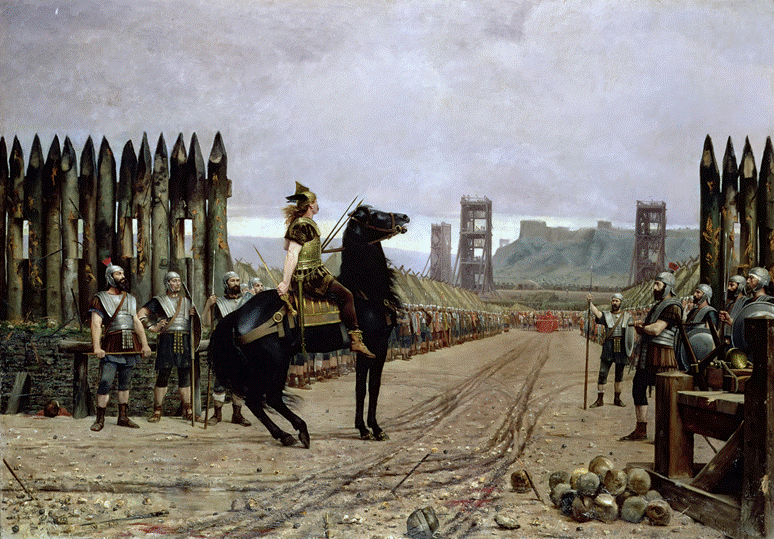

The Roman sense of cultural superiority was also bound up with this concept. To be Roman was to embody order, rationality, and discipline, in contrast to the perceived chaos or effeminacy of other peoples. Although he was dealing primarily with military affairs, the Roman author Vegetius comments at length on what separated the Romans from their foes. While there were a greater multitude of Gauls and the Greeks were superior in wisdom, Vegetius observed that, “the Romans owed the conquest of the world to no other cause than continual military training, exact observance of discipline in their camps and unwearied cultivation of the other arts of war”. Romans believed that warfare was the most perfect expression of their culture, and it was through this “exact observance” and inculturation of Romanitas that they conquered the Gauls and Greeks, eventually welcoming former foes into the Roman fold once they too had adopted these values.

The Interplay between Romanitas and Mos Maiorum

Though distinct, Romanitas and Mos Maiorum were deeply interconnected. The former provided the ideological content of Roman identity, while the latter supplied the moral and cultural framework that sustained it. Together, they created a powerful sense of individual purpose inextricably connected to the collective. Thus, a Roman citizen could see himself as a singular part or instantiation of a civilization destined to rule the world, not merely because of their military might, but because of the moral superiority conferred by adherence to ancestral custom.

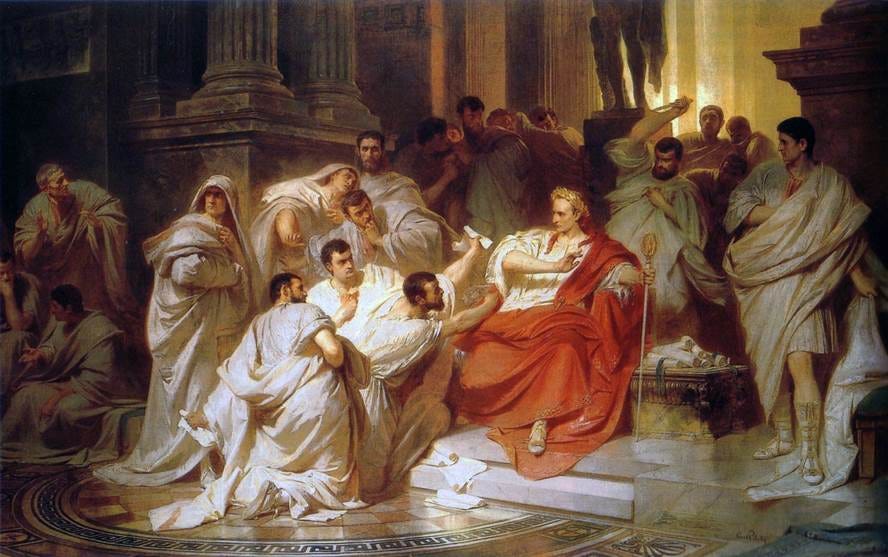

This interplay is evident in Rome’s political culture which always walked a delicate balance between innovation and tradition. Rome was rife with ambitious leaders who sought glory and reform, but these rarely stepped outside the strict bounds of ancestral precedent and tradition. reflecting the belief that Rome’s greatness lay in its ability to adapt to new challenges while remaining faithful to its values and traditions.

Understanding the Romans as a Civilization

By examining Romanitas and Mos Maiorum, we gain insight into the Romans’ conception of themselves as a people destined for greatness. Unlike the Greeks, who defined themselves through philosophy and art, or the Persians, who emphasized monarchy and divine kingship, the Romans defined themselves through moral and civic ideals. Their identity was not static but dynamic, capable of incorporating new peoples and practices, yet always anchored by the authority of the ancestors.

These concepts also explain the extraordinary resilience of Roman civilization. The Republic endured centuries of internal conflict and external threats, yet the ideals of Romanitas and Mos Maiorum provided a unifying social and political framework. Even under the Empire, when the constitution of the state has been fundamentally altered in everything but name, the rhetoric of ancestral custom and Roman identity continued to shape and provide legitimacy to those in positions of power. Augustus, for example, presented his regime as a restoration of tradition, claiming to revive the Mos Maiorum even as he transformed the political order into something very new.

Ultimately, the Romans saw themselves as the custodians of an exceptional moral and cultural inheritance which they were destined to spread throughout the world. Admittedly, the Patrician class remained a distinct group from other citizens insofar as they could trace their lineages back to founding members of the Roman state which placed them in the highest rungs of the social ladder, but social progression was not limited to birthright alone as Novi Homines or “New Men” such as Gaius Marius, Marcus Tullius Cicero, or the Emperors Trajan and Diocletian demonstrate that those who embraced Romanitas and the Mos Maiorum could rise to the heights of Roman society.

To be Roman, therefore, was not limited to those who lived in the city of Rome or to those in the provinces who held Roman citizenship, but to those who perfectly embodied what it means to be a Roman.

I'd add there was also the Roman sense of national destiny and their orneriness. An entire army is defeated at Cannae, tens of thousands killed. Most people would have begged Hannibal for mercy and thrown the gates open. The Romans started raising another army.

🫡