The Fall of the Roman Empire and the Rise of the Roman Church

How the Church filled the void left by Rome

The decline and fall of the Roman Empire remains one of the most profound turning points in the history of Western civilization. What had once stood as the pre-eminent political and military power in the ancient world collapsed under the weight of internal decay, external invasion, and spiritual exhaustion (previous article). Yet from the ruins of Rome there arose a new order – one that was not political but ecclesiastical, preserving the remnants of an ancient civilization and laying the foundations for what transformed into Christendom.

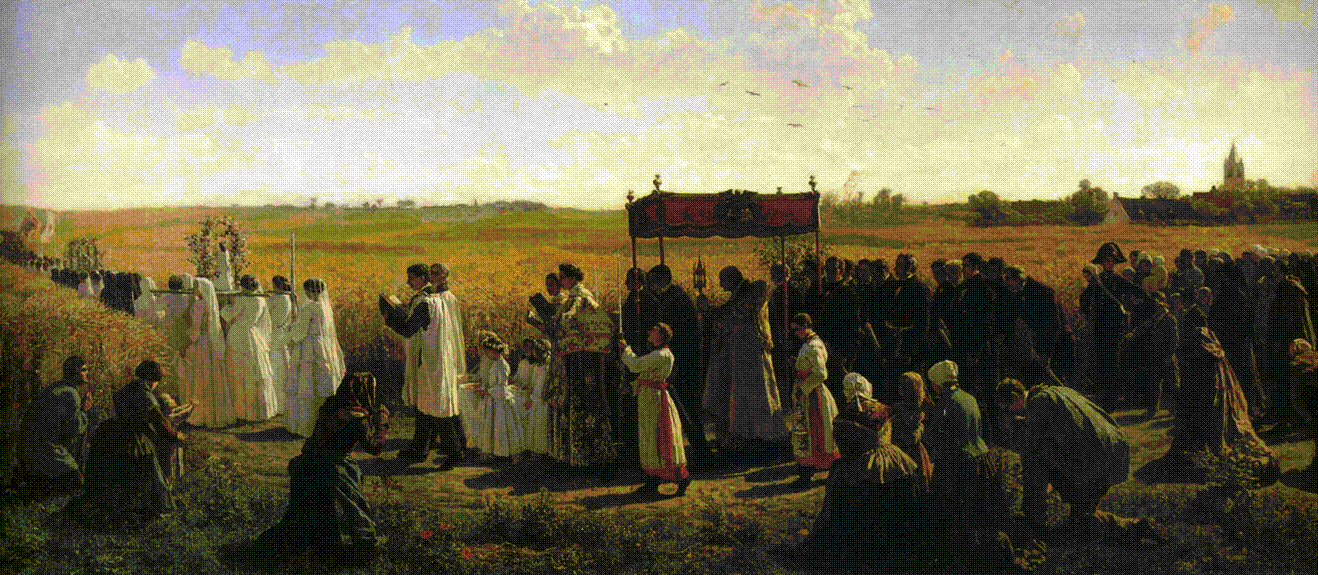

Filling the political vacuum was the Roman Church which safeguarded continuity of leadership, cultivated the arts and intellectual life, and guided the spiritual formation of its people – a charge the Church has borne across the centuries until the present day.

The Kingdom of God on Earth is Roman

In his magnum opus, The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo reflected on the fall of the Eternal City, writing extensively about the fate of empires. Within these pages, he reminded his audience of Roman and Christians alike that no earthly city, however glorious, could endure forever, as “The earthly city, which does not live by faith, seeks an earthly peace, and it makes war in order to attain peace”.

The decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD was the result of many interconnected factors (link), yet Augustine interpreted this event as ultimately directed by Divine Providence. Like many Christian contemporaries, Augustine believed that Rome was the prophesied “fourth kingdom” foretold in the Book of Daniel almost a millennium earlier, and it was upon Rome that “The God of heaven will set up a kingdom that shall never be destroyed… and it shall stand for ever”.

Bishops as Custodians of the West

As imperial authority waned, bishops assumed not only religious but also civic responsibilities. Due to their intellectual and rhetorical prowess, bishops such as St Augustine of Hippo, though primarily theologians, were often called upon to mediate civic disputes, administer justice, and negotiate political treaties with friend and foe alike. In his own Letters, Augustine frequently lamented the burden of these civic responsibilities which took him away from his spiritual obligations, and yet, he accepted these as part of his vocation as a shepherd of the Roman people.

The bishops’ jurisdictions were modeled on the traditional Roman administrative units known as dioceses and helped preserve continuity in social, political, and spiritual life. In cities and provinces that were once administered by imperial officials, the bishops often acted as de facto governors, judges, and defenders of their communities. Bishops also preserved the memory of Roman order primarily through the Roman liturgy, translating the civic virtues of Romanitas and the Mos Maiorum into a Christian context. They baptized the vestiges of Roman social and civic life with the new political order, ensuring that the West did not descend entirely into barbarism, and in doing so, "conquered their rude conquerors” – to paraphrase the poet, Horace.

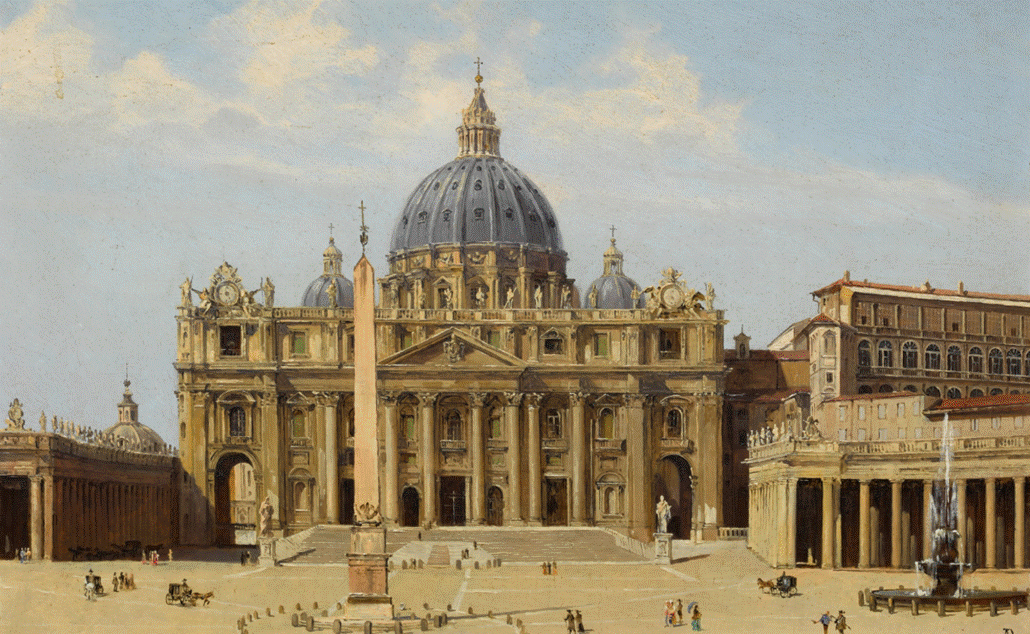

While the power and influence of the Western Roman Emperor diminished into the fourth and fifth centuries, the bishop of Rome emerged as a new principle of unity and authority in the West, effectively guiding the transition between the fractured world of late antiquity into the Middle Ages.

Defenders of Roman Order

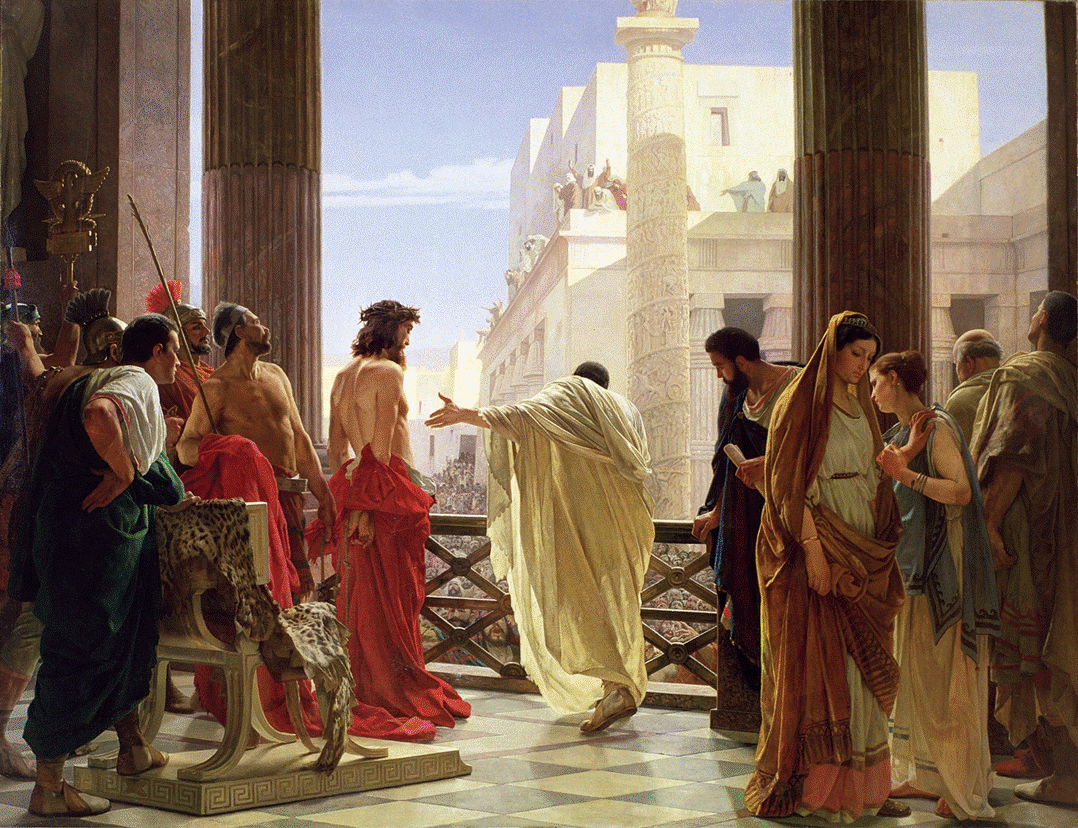

St Ambrose of Milan stands as one of the most striking examples of a bishop stepping into the political void as Rome fell further into decline. As a former Roman provincial governor himself, Ambrose was acclaimed bishop by popular demand in 374 AD, and from that moment he embodied the fusion of Roman administrative skill and Christian pastoral leadership.

Ambrose defended the authority of the Church against imperial interference in his confrontation with Emperor Theodosius after the infamous massacre at Thessalonica in 390 AD. The bishop barred Theodosius from the Church, compelling him to submit and to do public penance before being permitted to re-enter the Cathedral of Milan, reminding him that “The emperor is within the Church, not above the Church”. In this act of political defiance, the Ambrose safeguarded ecclesial independence from the state and reinforced the judicial precept that no man – whether slave or sovereign – is above the law.

Pope Leo the Great is another towering figure from these turbulent times. In 452 AD, when Attila the Hun advanced upon the city, Leo left the safety of his papal residence and confronted the fearsome warlord at the very gates of Rome. In this historic meeting, the Roman Pontiff is said to have threatened Attila with divine chastisement should he march upon the Eternal City, and to the amazement of those present, the barbarian king withdrew his army. Leo’s courage and leadership not only preserved the city from further devastation but also demonstrated the Church’s increasing authority in the temporal order, elevating the role of the papacy in the eyes of the people as the defender of the Church and Western Civilization.

Monasticism as Intellectual Formator of the West

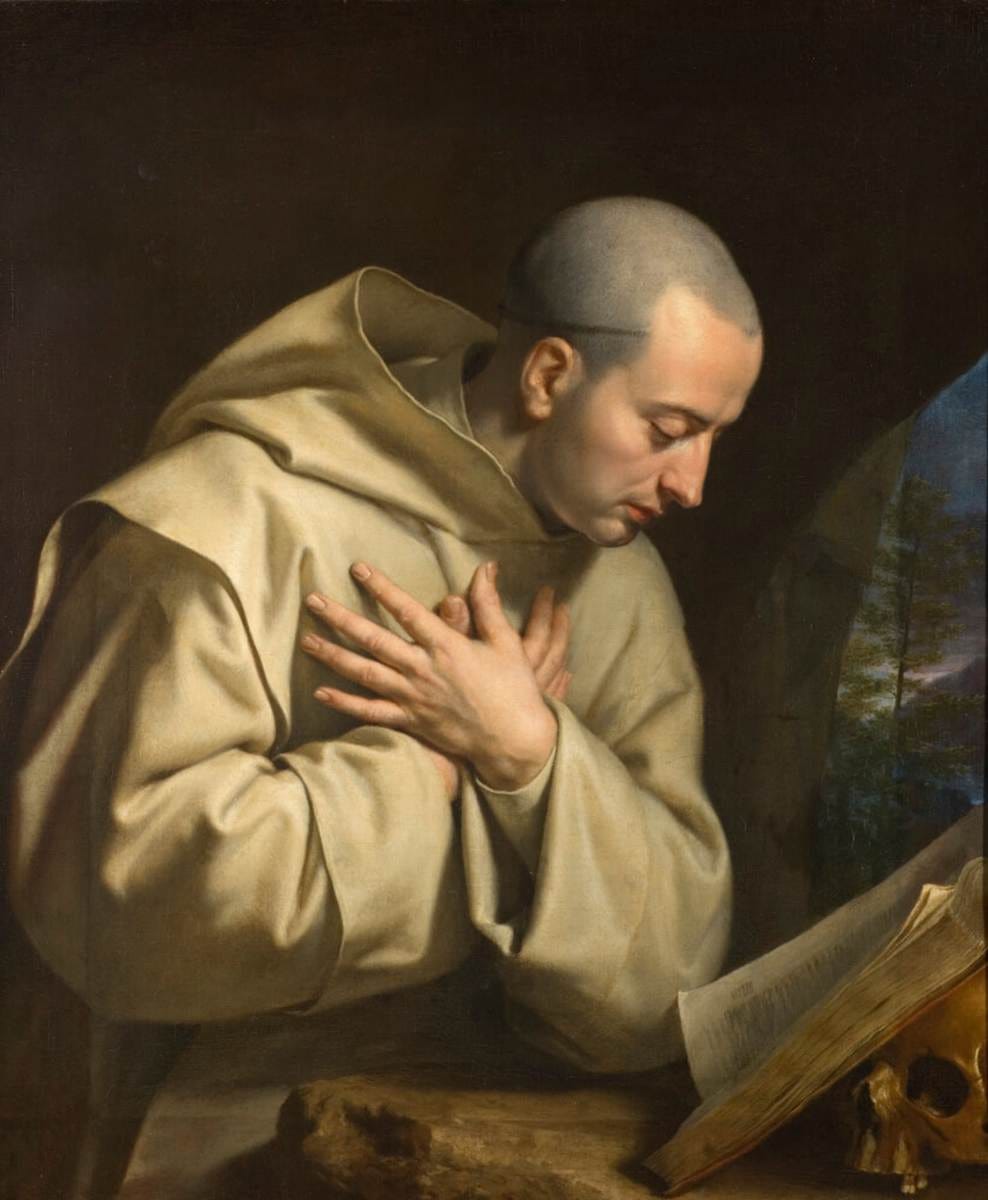

While the Magisterium preserved political order, monks preserved intellectual and spiritual life. The rise of monasticism in the West, particularly through figures like St Benedict of Nursia, created communities dedicated to prayer, labor, and study. In the silence of monasteries, monks transcribed ancient manuscripts, meditated on Sacred Scripture, and ultimately preserved the wisdom of the Greco-Roman world. Without their labor, much of classical philosophy, literature, and theology would have been lost to the ages and prevented any opportunity for a later Renaissance.

In his Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas Aquinas extolled the vital role of monasticism in preserving civilization, asserting that “Contemplation is greater than action, for it pertains more directly to the ultimate end of man, which is the enjoyment of God.” Yet this contemplative life was never isolated from practical engagement. Guided by the Benedictine motto ora et labora (pray and work) monasteries became hubs of agriculture, education, and hospitality. Wealthy families often entrusted their sons and daughters to religious orders, driving social, political, and religious reform across centuries and founding many of the great universities that endure to this day.

Thus, the monks were the intellectual formators of Western Civilization, transmitting both the intellectual heritage of the Greco-Roman tradition combined with Christian revelation. Armed with faith and reason, these men ventured fearlessly into what remained of the Roman empire and beyond to evangelize the Germanic peoples who they brought into the Christian fold, forming what would become the Holy Roman Empire.

The Church as the Perfection of the West

St Thomas Aquinas provides a profound observation in his Summa Theologiae that just as “grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it”, the Church built upon the powerful Greco-Roman foundations of Western Civilization and perfected it by Christian revelation. The Church became the spiritual bond that unified a politically fragmented West comprised of disparate kingdoms, tribes, and peoples.

The continued use of the Latin language created a shared vocabulary for law, theology, and governance, the liturgy provided a common rhythm of life, Roman theology provided a common framework of meaning, and her bishops and monks provided common institutions of cultural stability. In this sense, the rise of the Roman Church was not merely an historic aberration but an inevitable civilizational development. The Church became, in effect, the new and “perfected” Roman Empire.

Lessons for Modern Man

The fall of the Roman Empire is not a phenomenon confined to the pages of antiquity, but speaks urgently to the state of our modern world facing its own crises of meaning and order. Rome, which collapsed by abandoning Romanitas and the Mos Maiorum, reveals that so too does the West risk collapse if it abandons the Church and the Christian principles that built it.

History reveals that no matter how great, states fail, empires rise and fall, and kingdoms fracture, but to this reality St Augustine provides the sobering reminder that “the City of God shall endure forever”.