The Cost of Virtue

One Roman Emperor against the machine...

Saving an empire is difficult — and deadly.

In rare moments throughout history, a truly benevolent leader rises to power at the helm of a corrupt machine. Most of the time, the leader is transformed for the worse by the corruption around them. As Lord Acton so famously wrote:

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.”

But occasionally, someone rises to power and stands tall amid the swamp.

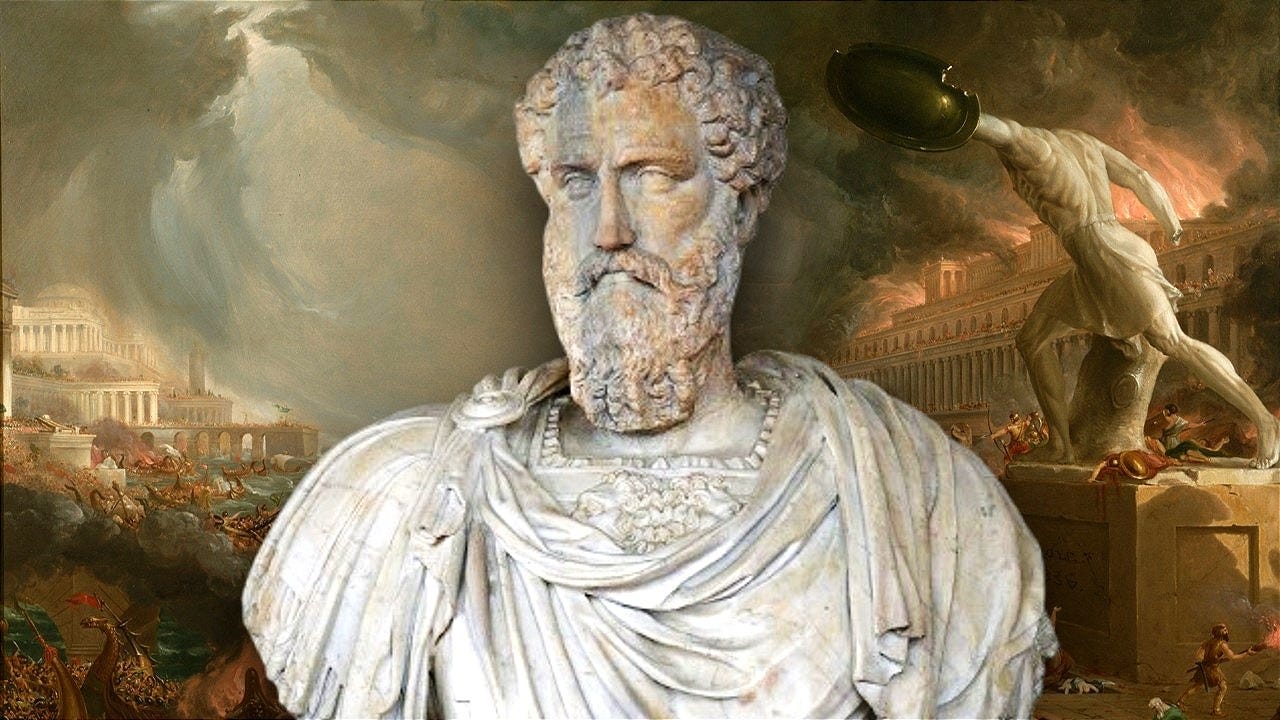

Emperor Pertinax was one such enigma in Roman history. With fearless idealism, he acted against the whims of the Roman establishment — and the machine turned against him…

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Rebound from Vice

Few Roman emperors were more despised than Commodus, the son of the revered philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius. Where Marcus wrote stoic meditations about wisdom and self-discipline, Commodus lived as a caricature of imperial excess.

His vanity was legendary: he renamed the months of the calendar after himself, renamed Rome “Colonia Commodiana,” and even styled himself as the reincarnation of Hercules, appearing in the arena as a gladiator to slaughter wounded animals and terrified men in mock combat. This divine delusion and cruelty alienated both the Senate and the people.

Rome, bloated and fracturing, needed a correction. The long humiliated Senate finally reached a breaking point. On New Year’s Eve of 192 AD, Commodus was strangled in his bathtub by the wrestler Narcissus under the direction of Commodus’ inner circle. He was posthumously declared a public enemy. Rome exhaled.

Into the vacuum stepped Publius Helvius Pertinax, a man of humble origins, born the son of a freedman in the Italian countryside. His rise through the Roman ranks was a classic tale of merit: first a schoolteacher, then an officer in the army, governor of provinces, and eventually prefect of Rome. At the age of 66, Pertinax ascended to the throne, chosen by the Senate to restore dignity and order to an empire on the edge of chaos.

Pertinax was everything Commodus was not. He was modest, disciplined, and virtuous to a fault. His ascension seemed to signal the dawn of a new age of responsible governance. Historians like Edward Gibbon and Cassius Dio portrayed him as a reformer — an echo of Marcus Aurelius — who sought to revive the stoic virtues that once guided Rome. Gibbon wrote of Pertinax:

“To heal, as far as it was possible, the wounds inflicted by the hand of tyranny was the pleasing, but melancholy, task of Pertinax.”

It was, however, a task bound to end in tragedy.

The Cost of Moral Courage

Pertinax immediately set to work unraveling the moral rot of Commodus’ rule. He slashed court expenses, reined in corruption, auctioned off the lavish possessions of the late emperor, and restored the currency’s silver basis to boost economic stability. He reversed unpopular taxes and promoted the idea that the prosperity of the empire lay not in extortion, but in economic productivity.

More than economic reform, Pertinax also attempted to restore military discipline, especially among the Praetorian Guard, the emperor’s personal bodyguards who had grown arrogant, soft, and politically dangerous.

The guards had come to expect enormous donativa (bribes or gifts) upon the accession of a new emperor. Pertinax, unwilling to perpetuate corruption, gave them only a modest appeasement.

This was his first fatal error….

The Guard was insulted. They saw not reform, but disrespect. Though the people and Senate admired Pertinax’s ideals, the power behind the throne, the soldiers, were growing restless.

Over a thousand years later, Machiavelli, noting that good deeds can provoke as much hostility as bad ones, reflected on Pertinax’s fate in The Prince:

“But Pertinax was created emperor against the wishes of the soldiers, who, being accustomed to live licentiously under Commodus, could not endure the honest life to which Pertinax wished to reduce them…”

Like children resenting parental discipline, the soldiers despised the reforms of Pertinax. But it was ultimately his mercy that was the final straw.

When multiple conspiracies against him were uncovered, he refused to mete out the harsh punishments typical of Roman justice. He pardoned the conspirators, believing that reform should come from virtue, not terror. However, his enemies saw this mercy not as wisdom, but as weakness. The Praetorian Guard, unafraid and unrestrained, plotted his end.

On March 28, 193 AD — just 86 days into his reign — 200 soldiers stormed the imperial palace. Unarmed and without protection, Pertinax stood his ground. According to Cassius Dio, he tried to reason with them, urging them to think of their duty to Rome. The guards ran him through with swords.

He died a reformer’s death: principled, defenseless, and betrayed.

A Darker Age

The murder of Pertinax marked the beginning of what became known as the “Year of the Five Emperors.” After his assassination, the imperial title was auctioned off by the very same Praetorian Guard who killed him. Didius Julianus, a wealthy senator, quite literally bought the throne, offering the Guard an enormous donativum in exchange for their support.

This farce further discredited imperial authority and plunged Rome into civil war. In the provinces, rival claimants rose: Septimius Severus in Pannonia, Pescennius Niger in Syria, and Clodius Albinus in Britain. Ultimately, Severus would prevail, but the lesson of Pertinax was not lost on him.

When Severus seized power, one of his first acts was to punish the Praetorian Guard by disbanding them and replacing them with his own loyal troops. He ruled as a military autocrat, crushing dissent and centralizing control. In contrast to Pertinax’s noble failure, Severus embodied a colder, more utilitarian version of rulership. His final advice to his sons, according to the historian Dio:

“Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all others.”

Pertinax’s brief reign is often remembered as a tragic prelude — a moment of clarity before the descending storm. His time in office was too short to cement much lasting change, but long enough to show that virtue alone cannot command obedience in a corrupt system. His reforms benefited the people, stabilized the economy, and restored a measure of sanity, but he lacked the ruthless pragmatism to outmaneuver the entrenched interests around him.

As a man, he was admirable. As an emperor, he was doomed.

In some ways, Pertinax’s fate reflects a broader historical pattern: when systems are rotten, honest reformers are either sidelined or sacrificed. Socrates in Athens, Cicero in the Roman Republic, Thomas More under Henry VIII: these were men of principle who entered the political arena with noble intentions and were ultimately consumed by it.

Dangers of Virtue

The death of Pertinax is not just a Roman tragedy. It’s a lesson in the limits of morality in power. In a government filled with self-interest, ambition, and inertia, goodness can be perceived as a threat, not an asset. The machinery of corruption has no mercy for well-meaning mechanics.

It asks a deeper question: Can a virtuous person lead a fundamentally broken system without being destroyed by it?

For Pertinax, the answer was no. His brief and brilliant attempt reminds us that political virtue is not just difficult, but deadly.

And yet, his name endured longer in admiration than most emperors who reigned for years. In 86 days, he showed what moral leadership could look like. And perhaps that, too, is a form of victory.

What your reflection on Pertinax touches is something far older than Rome. A person who rises in virtue becomes like a flame. To those who desire light, that flame is comfort and direction. To those who cling to the dark corners of their habits, the same flame feels like an exposure they cannot bear.

This is why the saints could walk into a room and some would be healed while others would flee or lash out. Perfection is not neutral. It reveals us to ourselves. The same reality that lifts us up can feel like judgment if we refuse to be lifted. In the highest sense this is why the tradition says the fire of Hell and the light of Heaven is one and the same. It illumines the willing and burns the unwilling. It is never the light that changes, but the heart that faces it.

So the seditious six are attempting to muster the pretorian guard to take out Trump as well as the guard’s new leader, Hegseth. Will they succeed? Who knows. But for certain, they will not stop trying.