The 3 Enemies of Civilization

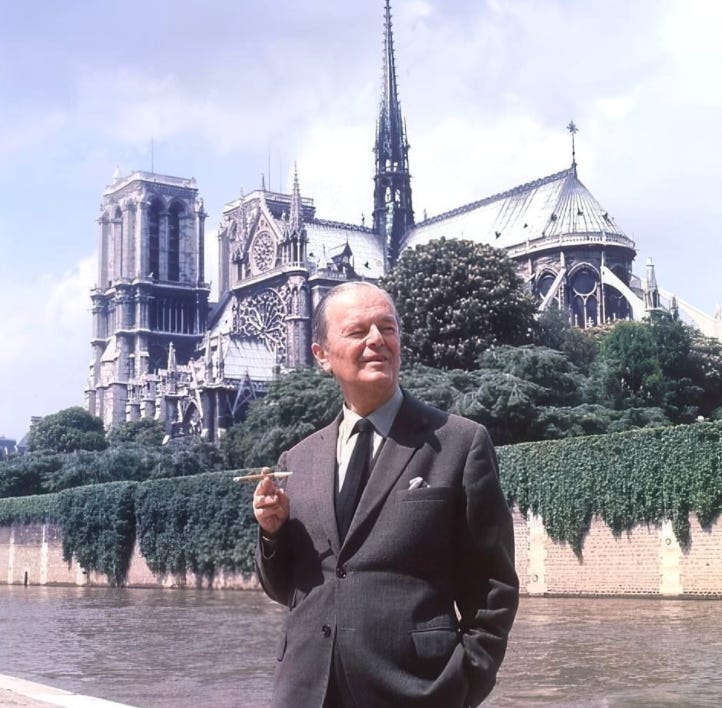

Kenneth Clark’s warning to the West…

Civilization is a fragile thing.

In his 1969 multi-part television series Civilisation, British art historian Kenneth Clark lamented this fact. The series, which outlines the history of Western art, architecture, and philosophy beginning with Rome's fall and ending in the present day, was a surprising success upon its release. It reached roughly 2.5 million viewers in Britain and 5 million in the US, and museums in both countries reported a surge of visitors following each episode.

But what was so revelatory about Clark’s T.V. show? What made his telling of art history resonate so much with general audiences?

More than anything, it revealed that Western Civilization was no accident — if it weren’t for a few key figures and events, the whole thing would never have come about. We made it through, in some cases, by the skin of our teeth.

Clark emphasized the danger wasn’t over, though. All societies battle three enemies that can topple even the mightiest cultures.

What are they, and how can we overcome them?

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Fear

The first enemy of civilization is simply fear — apprehension toward trying new things and overcoming challenges. Clark says:

“...fear of war, fear of invasion, fear of plague and famine, that make it simply not worthwhile constructing things, or planting trees or even planning next year’s crops. And fear of the supernatural, which means that you daren’t question anything.”

Fear paralyzes a people and stifles adventure, invention, and grand building projects. Societies that are afraid of innovation eventually stagnate and decay. Civilizations often reach an arrested state where their fears hold them hostage, preventing them from advancing culturally or technologically. Though tradition is important, a balance should be struck between custom and self-transformation.

Lack of Self-Confidence

The second enemy is a lack of self-confidence. Societies that lose appreciation for their founding principles decay into shells of their former selves, lacking identity. If a culture doesn’t believe it is worth perpetuating, then it simply won’t.

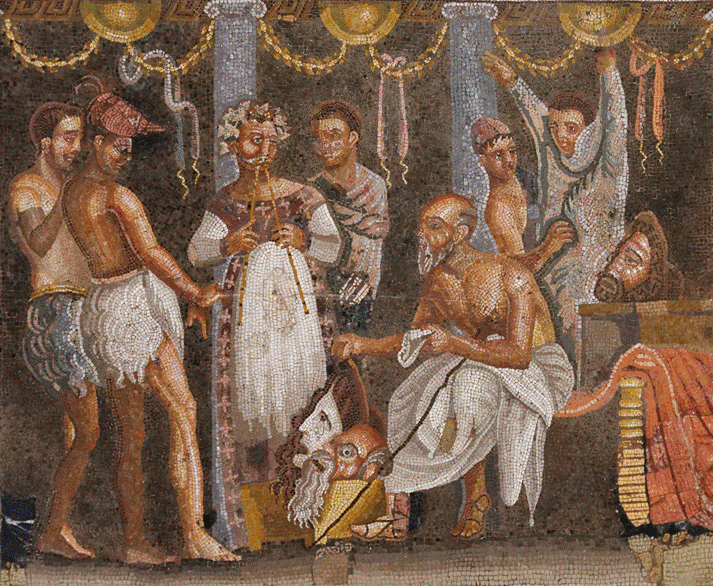

Clark saw the late Roman empire as a prime example of a culture that didn’t believe in itself anymore:

“The late antique world was full of meaningless rituals, mystery religions, that destroyed self-confidence.”

When traditions and rituals lose their connection to what inspired them in the first place, they become the performance art of a dying civilization. Cultures need to believe in something, or they will fall to ones that do.

Exhaustion

Finally, a civilization dies with exhaustion — the “feeling of hopelessness which can overtake people even with a high degree of material prosperity.” Decadence, moral degradation, and lack of belief in something greater leave a society questioning the point of it all. An aimlessness pervades society that is often only quenched by civilizational suicide.

Clark tells a story by a Greek poet who envisions an ancient town’s decline:

“There is a poem by the modern Greek poet, Cavafy, in which he imagines the people of an antique town like Alexandria waiting every day for the barbarians to come and sack the city. Finally the barbarians move off somewhere else and the city is saved; but the people are disappointed — it would have been better than nothing.”

An exhausted culture seeks novelty above all else — the humdrum of prosperity is too dull, so even destruction excites civilians in late-stage cultures.

Overcoming Our Obstacles

Enough doom and gloom — what’s the solution?

Clark draws a distinction between the “amenities” of civilization and the factors that caused it to prosper in the first place. For example, a society can be “dead and rigid” even while enjoying great wealth:

“People sometimes think that civilisation consists in fine sensibilities and good conversations and all that. These can be among the agreeable results of civilisation, but they are not what make a civilisation…”

Ultimately Clark says that flourishing civilizations have two things beyond a base-level of material prosperity: confidence and belief: confidence in one’s own society, which forms a cohesive identity; and belief in the foundational philosophy and laws of the culture, as well as a belief in the abilities of oneself and one’s countrymen to overcome obstacles together.

Clark gives the example of the incredible feats of Roman engineering as representative of a faith that each roman had in their institutions and laws. In particular, the way in which the stones of the Pont du Gard Aqueduct are laid shows not only a triumph of technical skill, but a vigorous belief in law and discipline, as well as a confidence in the ability to build great things.

But there’s something else all great civilizations share:

“Vigour, energy, vitality: all the civilisations — or civilising epochs — have had a weight of energy behind them.”

Though impossible to quantify, cultures on the ascendance are animated by a spirit of optimism. People are excited to build incredible monuments and statues, to start businesses, to create families, etc. They don’t have to rationalize their way into doing — they just do.

Ultimately, the ideas conveyed in Clark’s masterpiece Civilisation should inspire reflection about our own culture. Does the West believe in its foundational principles, laws, or philosophy? Is the West confident in itself, animated by a spirit of energy and vitality?

Or, is it fearful, timid, and exhausted?

This was serious food for thought. Thanks for sharing!