Rome and the West in Transition Through Mass Migration

Tolerance and Identity

This piece by Dr. David Engels is part of multi-part series, Rome Reloaded, exploring the striking parallels between ancient Roman society and our own. Enjoy!

Migration has always been a catalyst of historical change — and a test of cultural resilience. How societies deal with ethnic diversity, religious differences, and cultural unfamiliarity determines their internal cohesion.

Today, Western society sees itself as the epitome of openness, tolerance, and cosmopolitanism, but this claim is increasingly at odds with social realities. A glance at the final phase of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Empire shows how, even then, a society could fail because it overstretched its promise of integration. The parallels between Rome and the West are revealing — and disturbing.

It all starts with an anthropological principle: humans define themselves through belonging — to a family, a clan, a people, a religion, a civilization. This belonging is not arbitrary, but rests traditionally on elements such as origin, language, religion, tradition, and shared memory. It is these identity-forming characteristics that make solidarity possible in the first place and thus a social order that proves its worth not only in calm times but also in periods of crisis. For community does not arise from individuals merely bound by contract, but from naturally grown cultural communities that are aware of their history, their identity, and their boundaries.

Throughout history, the formation of collective identity has therefore always been associated with mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion: those who belong not only share the rights but also the duties and values of the community. This clear structure has become increasingly permeable in modern times, since, on the one hand, the principle of tolerance has been elevated to the highest civic virtue and, on the other hand, the time-honored societies of the West have been deliberately exposed to a wave of immigration unprecedented in centuries.

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Rome As a Model of Integration — And Its Limits

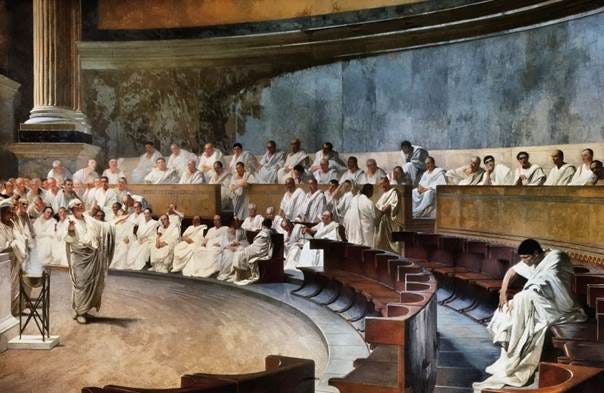

The early and middle Republic of Rome from the 5th to the 2nd century BC was characterized by a remarkable power of integration. Through numerous bilateral treaties, the gradual extension of civil rights, and the cultural acculturation of the subjugated peoples, Rome, which itself had emerged from the fusion of Latin, Etruscan, and Greek elements, became a state with an extremely complex but astonishingly stable identity.

Of course, even in the 3rd century BC, Roman citizenship was still intrinsically linked to origin, language, religion, and participation in the republican order: The “foreigners” who needed to be integrated came mainly from Italy and shared many basic ideas with the indigenous Romans; the naturalization of people from outside Italy remained a rare exception that barely affected daily Roman life.

However, in the 2nd century BC, conditions began to shift and threaten the authority of the traditional mos maiorum, or “custom of the ancestors.” The rapid territorial expansion of the empire, the mass migration of slaves, traders, freedmen, and craftsmen to the capital, and the influx of foreign cults and lifestyles increasingly overwhelmed the Roman model of integration. Rome quickly became the largest metropolis in the Mediterranean region — and in the process lost its cultural center, like many other Hellenistic cities that underwent similar developments.

Numerous contemporary authors such as Cicero, Sallust, Horace, and Petronius describe with growing unease the changes in urban life brought about by the influence of foreign groups. The Syrian merchants in the Subura, the Greek teachers in the elegant houses, the Mesopotamian diaspora, the Egyptian priests of Isis, and the countless slaves from all over the world who became Roman citizens as soon as their masters freed them — all of this was quickly perceived not as enrichment, but as a threat to the Roman order, all the more so as the increasing naturalization of foreigners strained the cohesion of the citizenry and, not least, the Roman social system, as Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote:

"Most were granted their freedom for free, because of their good behavior. And this was the most beautiful way of being released by their masters. A few paid a ransom, which they had saved up through honest and lawful trade. But in our time, this is no longer the case. The situation became so disorderly, and the dignity of the Roman state was so degraded and defiled, that even people who had engaged in highway robbery, burglary, fornication, or any other evil occupation could buy their freedom with this money and immediately become Romans." (Dion. Hal. 4,24, 5-6)

Soon, therefore, the first laws to expel non-Italian foreigners were discussed and, in fact, enforced twice, largely without consequence. However, there were also voices emphasizing Rome's humanistic obligation not to ban foreigners from residing in the city without good reason. Cicero, for example, considered the expulsion of foreigners to be inhumane, and the Stoic philosophers were in any case fond of a certain supra-political cosmopolitanism:

"But under the guise of utility, a mistake is very often made in politics [...]. Furthermore, it is wrong to forbid foreigners from residing in the city and to expel them from the country, as Pennus did with our ancestors (126 BC) and Papius did recently (65 BC). For it is right that a non-citizen should not be regarded as a citizen, as was proposed as law by the extremely wise consuls Crassus and Scaevola. But to prevent strangers from staying in the city is quite inhuman." (Cic., off. 3,47)

The West and the New Cosmopolitanism

Much like late Republican Rome, the modern West champions inclusion — but without the cultural guardrails that once made Roman integration viable. The similarities to today's situation are striking: there is no need to draw parallels with the spectacular migrations of late antiquity, when homogeneous groups invaded the Roman Empire, subjugated its citizens, and founded their own kingdoms. The analogies with the late Republic, with its gradual and largely peaceful migration process in a spirit of cosmopolitanism and economic needs, are much more appropriate.

For it is not only most Western states such as the US, but also supranational entities such as the European Union itself that is increasingly propagating an explicitly cosmopolitan ethos. The founding treaties speak of universal human rights, cultural diversity, and equality: European citizens are defined less as a historically grown community than bearers of abstract rights. Migration is — at least officially — not seen as a challenge to identity, but as an “opportunity” for diversity, with arguments oscillating between the economic need for cheap labor and a globalist duty of care. And of course, a similar case could be made for the US, which were arguably even more cosmopolitan by design since their foundation than the historically grown European nation states.

But the cracks are widening. Not only in the US, but also in France, Germany, Belgium, Sweden or the Netherlands, integration problems are becoming increasingly apparent. Crime, ethno-religious self-ghettoization, fundamentalism, moral decay, political radicalization — the demand for tolerance reaches its limits when cultural differences are not merely superficial but civilizational, and when the numerical ratios develop in such a way that extensive, quasi-autonomous parallel societies emerge that no longer need integration.

Where immigrants no longer want to become Westerners, but Westerners proactively relativize their way of life and values in order not to be accused of intolerance, the promise of integration breaks down. Tolerance is no longer seen in the literal sense of the word as “tolerating” the foreign, but as a demand for unlimited openness, and even more than that: anyone who even mentions cultural differences or makes demands in terms of integration policy excludes themselves from the society of the “juste milieu.” What begins as tolerance curdles into censorship; what is meant to foster inclusion ends in cultural self-erasure.

Rome and the Price of Tolerance

Mass immigration was by no means the only or even the most important reason for the outbreak of the Roman civil wars. But the divergence of the discourse on identity, the disappointment at seeing the once highly coveted Roman citizenship granted not only to Italians but to vast numbers of foreigners from all parts of the empire, and, of course, the general foreign infiltration of the metropolis on the Tiber did their part to destroy solidarity among citizens and create the conditions for decades of conflict.

It was not until the Augustan revolution that change came: the emperor established a cultural restoration program that, on the one hand, once again restricted the granting of citizenship and, on the other, created a new concept of identity: a “romanitas” which was no longer understood in ethnic terms but primarily in terms of civilization and was also accessible to non-Romans, the more they voluntarily adapted to the framework of what it meant to be a “Roman” — for example, by acquiring the language, practicing the state cult, joining the military, or making generous donations to urban infrastructure.

Thus, in his will, Augustus recommended that the manumission of slaves be restricted as far as possible so as not to further alienate Roman citizens:

"The fourth book finally dealt with the orders and instructions for Tiberius and for the state. Among other things, it contained an urgent warning not to grant freedom to too many slaves and thus fill the city with a motley crowd. Nor should they admit large numbers of applicants to the citizen registers, so that a clear distinction would remain between them and the subject peoples." (Cass. Dio 56,33)

Can we expect a similar reversal in today's West? Those who want to learn from history must have the courage to take it seriously. The Roman experiment shows that without cultural self-assurance, all tolerance leads to self-destruction. Europe and the US must decide whether they want to be a world state of human rights or a true political representation of Western civilization. Immigration can be enriching, but only if there is something to integrate into. Tolerance needs a center. And cosmopolitanism needs boundaries.

This text has first been published in the German language on “Corrigenda” and serializes updated elements from the book by the same author: “Auf dem Weg ins Imperium? Die Krise der Europäischen Union und der Untergang der römischen Republik. Historische Parallelen, Berlin / Munich, 2014 (Europa Verlag Berlin), 544p.”

Hello, I am trying to subscribe as a monthly payer but it appears you only accept Apple Pay. I don’t use Apple . Thanks!

The article does a great job showing how Rome mirrors today’s debates on migration and identity. What stands out to me is that Rome’s real crisis wasn’t just about newcomers, but about the weakening of the common framework that once held the Republic together. Without that shared base, integration stops working. That seems to be the key to understanding both Rome’s fall and the challenges we face now.