Romanization and Globalization

Cultural Vulgarization and Political Imperialism

This piece by Dr. David Engels is part of multi-part series, Rome Reloaded, exploring the striking parallels between ancient Roman society and our own. Enjoy!

“If someone wants to see the whole Mediterranean world, he must either travel the entire globe to look upon it that way, or come to this city, to Rome. […] So countless are the cargo ships that arrive here, bringing goods from every land from spring to late autumn, that the city appears like a common marketplace of the entire world. Cargoes from India, even—if you will—from ‘Happy Arabia’ arrive in such abundance that one might think nothing but bare trees were left behind there, and that the people would have to come here to reclaim their own products should they need them.”

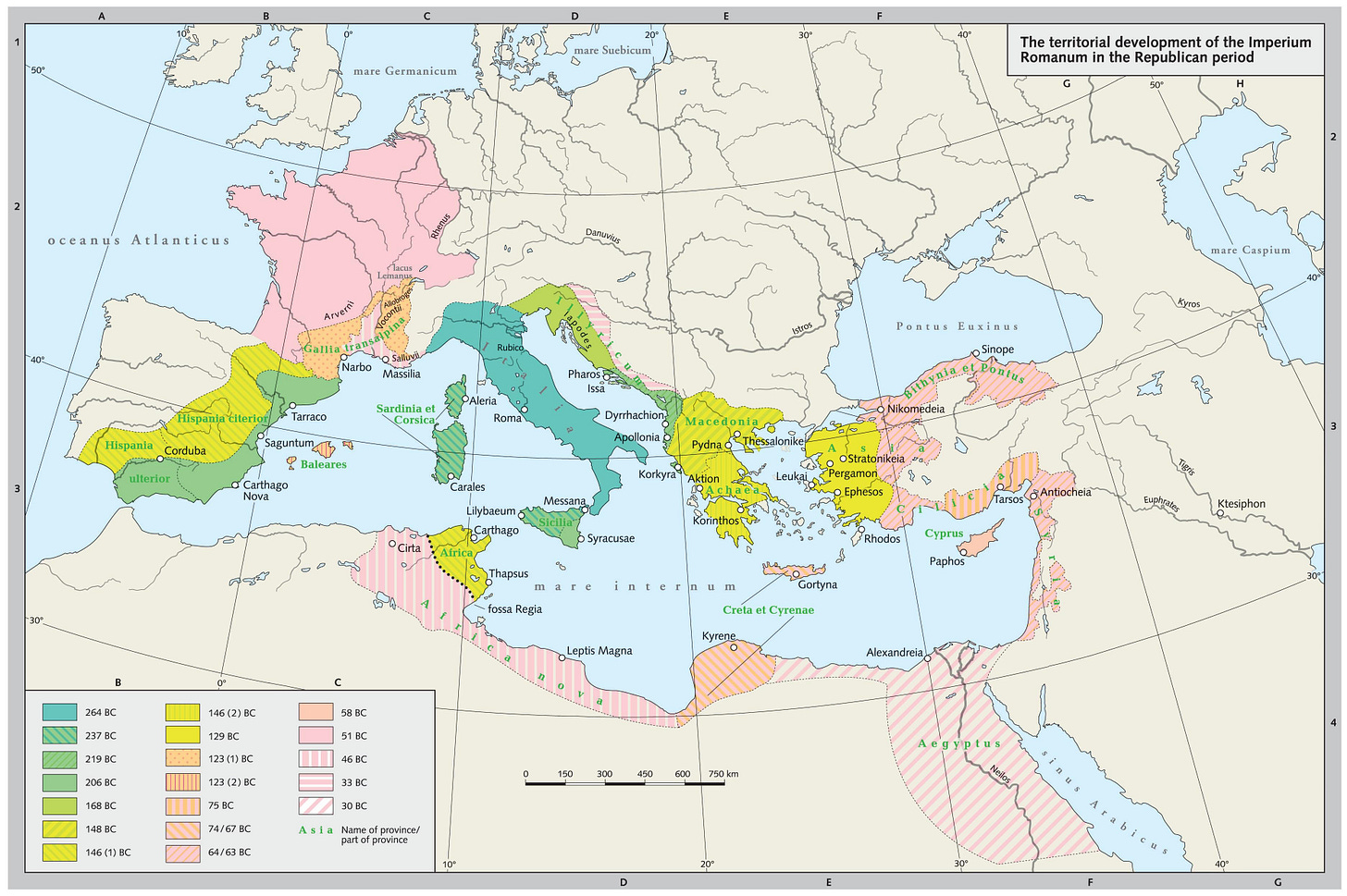

This famous passage from Aelius Aristides’ “Roman Oration” illustrates just how interconnected the ancient world already was. And although the debate over whether the ancient economy was “primitive” or “modern” remains unresolved, there is little doubt that beyond the tight web of economic interdependence within the Greco-Roman oikoumene, significant processes of acculturation also took place. These led to a genuine civilizational “globalization” of the Greco-Roman world stretching from Britain to Egypt and from Hispania to Syria (and, in the Hellenistic era, deep into Iran).

Yet even then it was clear that one could hardly speak of true “globalization” in the sense of an equal give-and-take. Cultural unification in the Mediterranean world went hand in hand with Hellenization and Romanization—just as today’s “Western world,” with its global reach into Asia and Africa, operates under the sign of Americanization.

In the twenty-first century, globalization has become the all-dominant reality of international politics, economics, and culture. The nation-state seems to fade, cultural identity becomes a matter of personal taste, and economic efficiency triumphs over historical loyalties. This development is often hailed as progress, openness, and modernity. Yet comparison with Romanization in the late Republic and early Empire shows: globalization is not a new phenomenon. Rome too once faced the challenge of stabilizing a vast and ethnically diverse empire through cultural standardization, consciously deploying cultural homogenization as a strategic instrument of power.

else.”

Reminder: you can get tons of useful members-only content and support our mission for a few dollars per month 👇

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Romanization as a Civilizing Project

“Romanization” was a strategy of cultural integration that bound political authority to cultural hegemony with great effectiveness. Across the empire, Roman baths, temples, theaters, roads, and administrative buildings were constructed. Latin spread across the West (while Greek remained dominant in the East). Roman law gradually reached even the smallest villages. Roman dress, dining habits, and architecture became standard not only for elites but increasingly for the general population—though one should not forget that this “Roman civilization” was in many respects already a simplified and flattened version of the Hellenistic world culture spread earlier by Greek traders and colonists and Macedonian soldiers.

This homogenization, however, was no consensual process. It was not based on mutual exchange but on hierarchy. Rome was the center; the provinces, the periphery. Those who wanted to advance had to adapt—not by legal compulsion, but under strong social pressure. The cultures of the conquered were gradually marginalized, their traditions reduced to folklore or given a Roman façade behind which the original substance faded away. The Roman model was universal, but it was also imperial. Alongside the conquest by legions, it served as a crucial method of securing power, as Roman authors themselves sometimes admitted not without criticism. Tacitus, for instance, in his Agricola, described how his father-in-law, governor of Britain, used cultural Romanization as a tool of domination:

“The following winter was spent on highly beneficial measures. To accustom the people, scattered and rough and thus prone to war, to quiet and leisure through pleasures, he encouraged them personally to build temples, forums, and houses, assisting them with public funds, praising the energetic and reproaching the idle: thus there was competition for honor instead of compulsion. Moreover, he had the sons of leading men instructed in the liberal arts, and he preferred the intellectual talent of the Britons to the industry of the Gauls, so that those who had just rejected the Roman language now longed for its eloquence. From that time on, our style of dress was esteemed, and the toga was often seen. Step by step they were led toward the allurements of vice—porticoes, baths, and the elegance of banquets. And this was called ‘civilization’ by the ignorant, though it was but a part of their servitude.”

Globalization Today: The New Empire of Standards

In today’s Western world we see something similar—particularly in Europe. European integration is pursued not only as a political but also as a cultural project. Uniform standards, harmonized education systems, language adjustments, legal convergence—all this is promoted in the name of efficiency, connectivity, and the “European idea,” radiating out to the wider world. But the cost is high: national cultures are leveled, regional traditions vanish, historical distinctiveness is dismissed as an obstacle. Most of all, homogenization today is shaped decisively by the cultural dominance of the United States.

English has become the global lingua franca; European bureaucratic jargon displaces the inherited political and cultural vocabulary of nation-states. In music, advertising, politics, art—and of course in clothing, lifestyle, and architecture—an aesthetic uniformity prevails reminiscent of Roman times. Over all this presides a new transnational elite: mobile, cosmopolitan, thinking in English—and increasingly detached from the deep cultural roots of ordinary populations, not only in Europe or the broader West but across the globe, where American cultural and political influence long ago eclipsed the last traces of Europe’s colonial legacies.

Civilization or Cultural Erasure?

What should we make of this? On the one hand, American civilization is ultimately just a diluted variation of English, and thus European, culture. Complaints that the world has become “American” overlook the fact that it has thereby also become more “European”—for better or worse. Yet resentment grows among those who see their own cultures pushed aside by Netflix and TikTok, from Himalayan villages to African savannahs. Their anger is directed not just at the U.S. but at the entire West, however reluctant U.S.-critical Europeans may be to admit it.

The cultures of the Gauls, Iberians, Thracians, or Numidians were not wiped out either, but they were reduced to decorative supplements and everyday trivia. Celtic gods were assimilated into the Roman pantheon; local festivals reshaped; native buildings dismantled; local languages overlaid with Latin and Greek loanwords. The result was a world outwardly unified but inwardly estranged—not only on the periphery but even in parts of Italy that had once been proud allies, until their languages too died out as they became Romans not only in law but in speech

So too with modern globalization. It promises diversity but produces uniformity; it celebrates difference while generating sameness. The cultural diversity of peoples is praised rhetorically but undermined in practice—through economic pressure, linguistic dominance, and legal harmonization. Fashion, consumer goods, music, TV shows, apps, and standards look the same from Lisbon to Tallinn, directly or indirectly of American origin, and radiating across the globe.

For the individual this means both relief and alienation. One can find one’s way anywhere, but feel at home nowhere. Local distinctiveness vanishes, local identity becomes a leisure accessory—a bit like McDonald’s “special local offers,” transparently feigned gestures of rootedness. What remains is a global web of interchangeable lifestyles.

Resistance and Adaptation: Two Sides of the Same Coin

As in Rome, reactions today are ambivalent. Elites celebrate globalization as progress, while numerous movements—especially in Europe—resist it for diverse ideological reasons: nationalists, regionalists, traditionalists, even environmentalists. In late Republican and imperial Rome it was no different. Resistance arose not only from “barbarians” at the borders, but sometimes from within the Mediterranean heartland itself. Yet the pull of the center was overwhelming—and tellingly, even opposition to Romanization often expressed itself in increasingly Roman forms. Today too, “patriotic” bloggers across Europe and beyond rail against American cultural dominance—ironically, in English.

Is there any chance, at least in Europe, to forge a degree of civilizational unity necessary to stand as an equal and resilient civilization-state alongside China, Russia, the U.S., and India—without borrowing America’s cultural template and thereby discrediting the entire project from the start? Perhaps. It must be attempted for as long as possible, though hopes should not run high. One thing, however, seems clear: what Ortega Gasset once described in grim terms as the end-state of a globalized and Romanized Mediterranean world is reappearing today as the outline of a late Western civilization looming on the horizon of history:

“But the most dreadful evidence and system of this uniform, soulless way of life that spread across the Empire is to be found in a field where we least expected it and where, as far as I know, no one has yet looked: language. […] Among the non-Hellenized parts of the Roman people there prevailed an idiom called Vulgar Latin, the mother of our Romance languages. […] Its first hallmark is the incredible simplification of grammar compared with classical Latin. […] A language without light or warmth, without force of conviction or spiritual fire, a dreary tongue stumbling in the dark. Its words are worn and angular like old copper coins, their endless circulation through Mediterranean taverns written on their faces. How many empty, joyless, everyday existences can one sense behind this barren linguistic construct! The other wretched feature of Vulgar Latin is its uniformity. […] To be sure, there were Africanisms, Hispanisms, Gallicisms. But this only shows that the core was everywhere the same, despite vast distances, limited exchange, poor transport, and the lack of literature. […] And how could such uniformity have arisen except through a general flattening of life, where existence was reduced to bare essentials and individual lives drained of content? Vulgar Latin lies in our archives as a chilling fossil, a witness to a time when history itself withered under the monotonous rule of the vulgar.”

Hello friend! I’ve been on Substack for about 2 weeks now, and I’m looking for interesting people!

I thought I’d drop a comment and introduce myself with a article, it’s about the Tartarian Empire, an empire bigger than the romans:

https://substack.com/@jordannuttall/note/p-175551254?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action