Proscription and Polarization

Political persecution in the late Roman Republic and today

This piece by Dr. David Engels is part of multi-part series, Rome Reloaded, exploring the striking parallels between ancient Roman society and our own. Enjoy!

The term “proscription” is hardly used in contemporary political discourse anymore: it seems too closely associated with remote antiquity, dictatorship, and totalitarianism to be used to describe the state of the supposedly enlightened and progressive Western world.

And yet there are increasing signs that the conditions of the late Roman Republic are repeating themselves in this area as well, and that we are witnessing a disturbing return of mechanisms that developed into a veritable instrument of rule in the 1st century BC: the targeted ostracism and social elimination of political opponents – legally veiled, amplified by one-sided media coverage, and enforced by a complying administration.

For what began in Rome under Marius, Sulla, and the Second Triumvirate as bloody practice is increasingly appearing in modern democracies as a psychological, social, and legal means of pressure. Admittedly, opponents are no longer declared outlaws on tablets in the Roman Forum, expropriated, and executed — it would be distasteful to draw parallels here — but the principle has remained the same: denunciation, stigmatization, and exclusion from public life, with the aim of not to debate political alternatives, but to eliminate them, often enough combined with the destruction of at least the social, professional, and financial foundations of their proponents.

This development is not accidental, but structural. For in eras when cultural identity, political decency, and shared values erode, political discourse becomes increasingly dominated by the crude will to power. It is worth taking a closer look at the ancient origins of this development — not to “learn from history,” but to understand why certain mechanisms continue to operate independently of the spirit of the times.

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

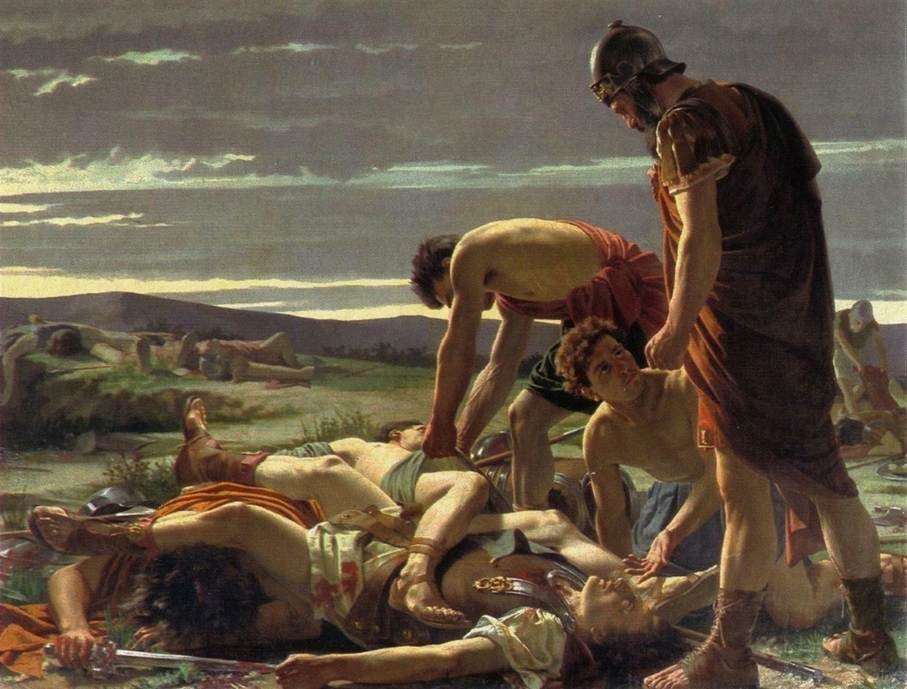

The Birth of Proscription

The term proscriptio originally referred to the public posting of property for auction. In a political context, the term took on a dramatic new meaning under Lucius Cornelius Sulla (dictator 82-79 BC): After his victory in the civil war against the supporters of the “Populares” under Gaius Marius, who in turn had persecuted, expelled, and in some cases murdered the conservative “Optimates,” Sulla officially published lists with the names of thousands of his opponents. Anyone who handed them over or killed them was financially rewarded, while their property fell to the state and was auctioned off, and their children were disinherited.

However, the cruelty of this system was not merely a temporary eccentricity; it was part of a systemic transformation process that had already been initiated under the Gracchi, in which the Roman Republic was transformed from a republic based on the mos maiorum, or “custom of the ancestors,” and their countless rules of decorum, to the practice of naked violence. The political opposition was no longer treated as a legitimate interlocutor, but as an enemy, a threat, an obstacle to be eliminated in order to finally create a tabula rasa for the unimpeded pursuit of one's own goals.

The instrument of proscription was even more brutal under the Second Triumvirate (43-33 BC), consisting of Octavian (later Augustus), Marcus Antonius, and Lepidus. In a politically unique move, the three men agreed on a list of around 300 senators and over 2,000 knights who were to be eliminated — not only as an act of political revenge against Caesar's murderers and the Republicans, but also to finance their own troops and to consolidate their power, with outright horse-trading taking place between the triumvirs, who often sacrificed their own friends in order to eliminate dangerous enemies who were supporters of one of the other triumvirs.

The case of Cicero is an eloquent example: although Octavian had personally been promoted by Cicero, he sacrificed him under pressure from Antony, who in return gave up his own followers – a decision that Octavian later publicly regretted as sole ruler, although he had undoubtedly benefited from it (freely adapted from Frederick II's dictum that Maria Theresa shed a few tears during the first partition of Poland, but took her share very well: “She wept, but she took nonetheless.”) Cicero was murdered while fleeing, his head and hands displayed in the forum, a cruel sign of power that also signified the symbolic death of Roman oratory as a genuine political force. The republic as a constitution effectively ceased to exist — what remained was a battleground of political interests, where personal power constellations alone decided, not the law, and where even ideological opposition increasingly took a back seat to purely pragmatic and personnel-related political constellations.

Proscriptive Structures in Modern Times

The parallels to the modern era are evident — even if they take different forms, since history never repeats itself in a simplistic manner, but rather analogous patterns reveal themselves under ever-changing conditions.

Totalitarian socialism in the Soviet Union, National Socialism, fascism in Europe, but also democratic societies such as the US during the McCarthy era resorted to mechanisms similar in structure and effect to Roman proscriptions: blacklists, professional bans, social ostracism, confiscation of property, travel restrictions, character assassination – and, of course, in the worst case, imprisonment, torture, and death.

Although the era of totalitarianism is now over, this should not reassure us. While in ancient times the forum was the place of denunciation, and in the 20th century it was the official gazette, today it is primarily the internet: Social media such as X or TikTok, journalistic cabals, and NGO networks are taking over the function of state ostracism.

The consequences are also different: with a few exceptions, the worst that can be feared is the loss of one's job, circle of friends, social respect, bank account, or — for a few months or years — one's freedom; no one in the West has to fear internment or execution.

The justification has also changed — from “saving the republic” to “defending the rule of law,” from “protecting morals” to “preserving human dignity,” from “reorganizing the state” to “resilient democracy.” But sadly, the core remains the same: those who do not toe the line are increasingly removed from public life — and although the methods used today are bloodless, their effectiveness in terms of mass politics is hardly any less than it was two millennia ago — just remember the terrible time of the COVID-19 measures, when denunciations were not uncommon even within families.

The Hunt for Political Dissidents

In the world of high politics, obvious examples catch the eye: think of Poland under the government of Donald Tusk, where within weeks of taking office in December 2023, the public media was taken over, countless conservative officials, journalists, and employees were removed from their posts, their communication devices were confiscated, and legal investigations were launched against them — to the applause of the EU institutions.

In Romania, the presidential election was annulled due to the imminent victory of a candidate considered too conservative and close to the Kremlin — under obviously flimsy legal pretexts. In France, the most promising candidate for the presidency was excluded from the next election for the most transparent reasons.

And in Germany, not only are new denunciation websites regularly launched to report politically unpopular individuals, but laws are also being passed to remove officials who are ideologically “questionable” from office, reversing the burden of proof of their functions. Even sympathizers of the country's second-strongest party are increasingly being persecuted professionally and socially, regardless of whether they behave in accordance with the law or not: police officers, civil servants, and teachers are losing their jobs, associations are losing their funding, writers are losing their bank accounts — solely because of their ideological proximity to a party or ideology that has been labeled undesirable.

Even in the US, once a model of liberal rule of law, dozens of former employees of political opponents have been charged under Joe Biden's presidency. Countless proceedings were and still are being brought against former presidential candidate Donald Trump – and this in a political climate where terms like “fascist,” “extremist,” and “threat to democracy” have long since become battle cries of partisan rhetoric.

From Rule of Law to Civilizational Fatigue

Of course, like a boomerang, the dismantling of the rule of law by a triumphalist left can also turn against itself, as recent events in the US have shown: Even the “US DOGE” is nothing more than a pseudo-libertarian instrument for “proscription” of countless individuals and initiatives that are no longer ideologically acceptable to the new Republican administration, and it is to be expected that analogous political upheavals in “old Europe” could well adopt similar methods, as already announced by Nigel Farage.

As in the Roman Republic, increasing ideological polarization is followed by the institutionalization of selective application of the law. Laws are no longer regarded as universal, but as instruments of political victory. The rule of law becomes a facade behind which only interest politics is hidden. Those who think differently are no longer refuted by arguments, but marginalized by administrative measures.

Democracy — or rather, those who believe they have a monopoly on democracy for their ideological camp — defends itself by beginning to act like its enemies or by “anticipating” their allegedly impending measures. But the stability that is bought through exclusion is deceptive, because it is not achieved through consensus, but through exhaustion.

It is one of the naive reflexes of historiography to believe that we can “learn” from history. Anyone who has studied the frighteningly uniform development of the great civilizations knows that, in truth, the fundamental dialectical mechanisms of history repeat themselves over and over again because the anthropological constants do not change. Power remains power, fear remains fear, and once someone has the opportunity to eliminate their opponent, they will rarely refrain from doing so when all boundaries of traditional decency have disappeared.

Sooner or later, one side will prevail in the West too — not because it is more convincing, but because it acts with greater determination, ruthlessness, and uncompromisingness. And the people? As so often in recent history, it will not decide, but will bow down, one fears. Not out of conviction, but out of fatigue. Out of a desire for peace, order, and security. Rome knew this fatigue — it was called Augustus. Our time will find its own word for it.

This text has first been published in the German language on “Corrigenda” and serializes updated elements from the book by the same author: “Auf dem Weg ins Imperium? Die Krise der Europäischen Union und der Untergang der römischen Republik. Historische Parallelen, Berlin / Munich, 2014 (Europa Verlag Berlin), 544p.”

Anything true is the visible carrying the invisible. Proscription is terrifying precisely because it inverts this: the visible name posted in the forum, or blasted online, becomes a totalizing judgment that severs a person from all higher meaning. It is the anti-truth.

A gathering not toward reconciliation, but toward erasure.

Anything true is the visible carrying the invisible. Proscription is terrifying precisely because it inverts this: the visible name posted in the forum, or blasted online, becomes a totalizing judgment that severs a person from all higher meaning. It is the anti-truth.

A gathering not toward reconciliation, but toward erasure.