Is Beauty Mathematical?

Math, beauty, and the music of spheres

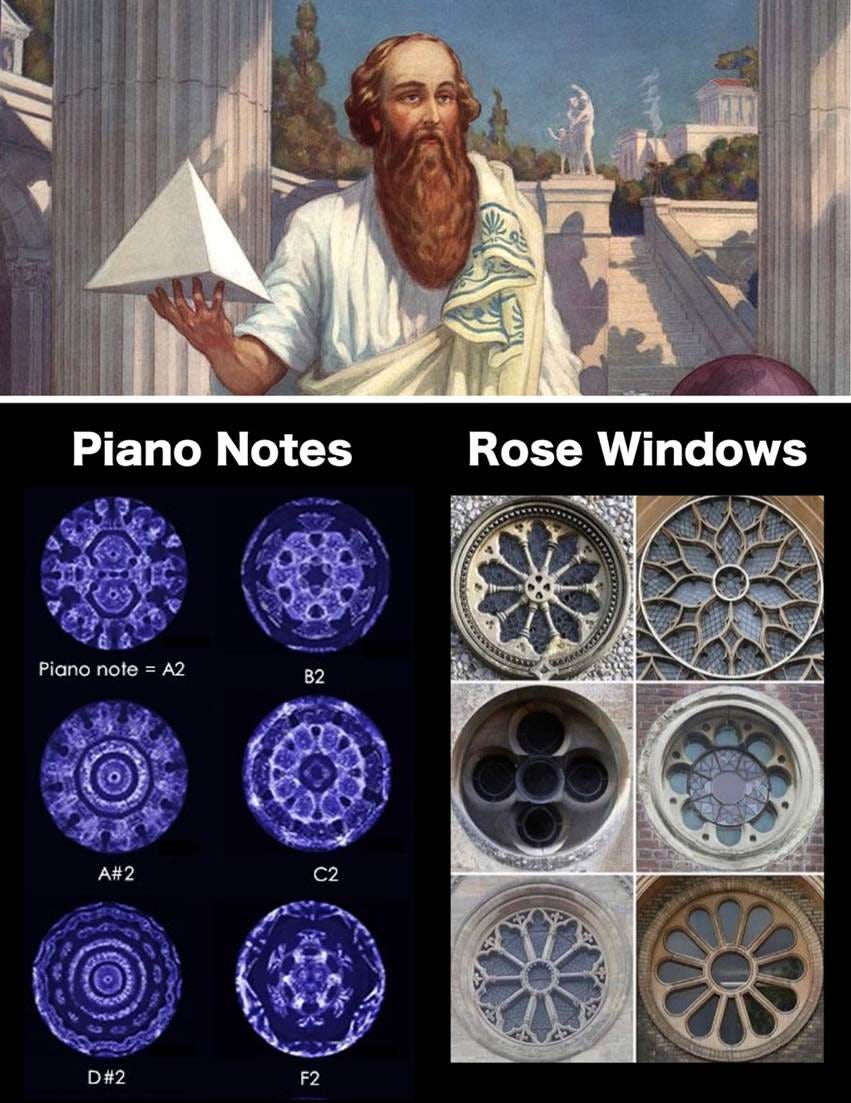

When you look at something of physical beauty created by past cultures — a gothic façade, a Roman portico, a rose window — you might notice something that connects them, even if they’re separated by centuries or continents.

Mathematics.

Many ancient and medieval structures that you’re familiar with are pleasing to the senses because they were designed for that purpose — not just by the inspired and emotive hand of an artist, but with precise symmetries and ratios of a mathematician. In other words, they produced a kind of beauty that can be measured.

That’s because past societies were keenly aware of something fundamental about how we perceive reality. To them, math, beauty and the human senses were deeply connected, and the artist’s job was to discover their point of intersection.

It all started when a man named Pythagoras discovered something utterly mind-blowing about reality: the universe is not made of matter, but music…

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Music of Hammers

Sometime around the middle of the first millennia BC, an eccentric thinker and polymath named Pythagoras was walking past a blacksmith’s forge. Amidst the clanging of hammers, he noticed something — from time to time, the hammers would emit a certain harmony that was strangely pleasing to his ears.

When he investigated further, he realized what it was. Two hammers, one precisely twice as heavy as the other, produced a harmonious sound when banged in unison against the metal.

As the story goes, Pythagoras went on to record that a 2:1 weight ratio produces an octave (notes separated by an octave sound alike). Likewise, a 3:2 ratio creates a perfect fifth, and 4:3 a perfect fourth. This discovery would later evolve the musical scale we use today.

But it wasn't just weight. Pythagoras found that a note's pitch is inversely proportional to the length of the string that produces it. Certain sounds, he had uncovered, are harmonious together because of a mathematical relationship between them.

This got him thinking — if music is essentially math, perhaps the universe itself is also governed by mathematical patterns?

The Music of Spheres

Eventually, Pythagoras came to the idea that the universe and everything in it is vibrating. As math and music are interconnected, the universe too is musical, and physical matter is merely music solidified. Indeed, he developed a theory called the "music of spheres," intuiting that celestial bodies hum a kind of music as they move, unheard by human ears:

"There is geometry in the humming of the strings, there is music in the spacing of the spheres."

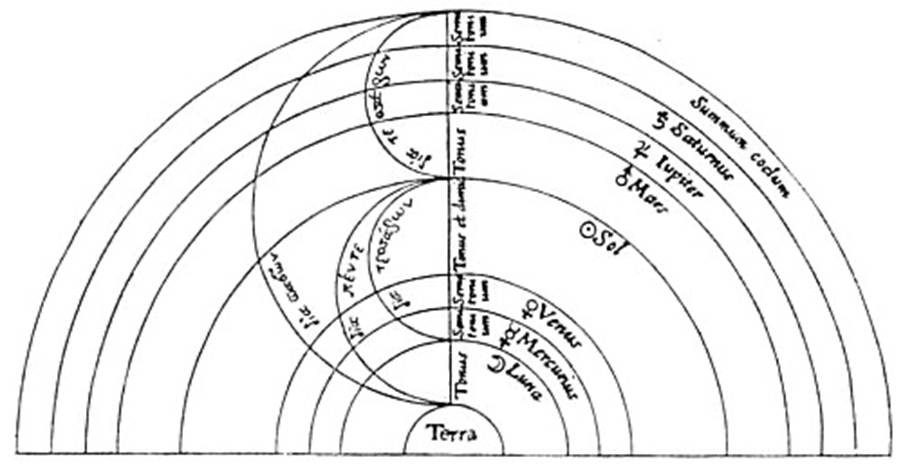

Pythagoras and his followers went as far as to map the sun and planets, assigning each a unique tone based on their orbit and distance from Earth. Their various distances were musical intervals, and thus the planets were arranged in a musical scale of their own. We cannot hear this music with our ears, but it's heard by the soul.

Pythagorean thinking of this kind carried into the Middle Ages with Boethius, polymath of the early 6th century, who went even further. In his great musical treatise, “De Institutione Musica”, he elaborated the three kinds of music:

1. Musica mundana: the unheard harmony produced by the motion of celestial bodies

2. Musica humana: the harmony between body and soul

3. Musica instrumentalis: audible music produced by instruments or human voices

These weren't just radical, isolated theories. This was a worldview that permeated society for centuries, and people believed the universe was bound by a mathematical, musical harmony.

For example, if you went to university in the Middle Ages, you learned music not as an art, but as one of four sciences. The quadrivium —arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy — were grouped together as the second stage of any serious education (after pupils had mastered the trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric).

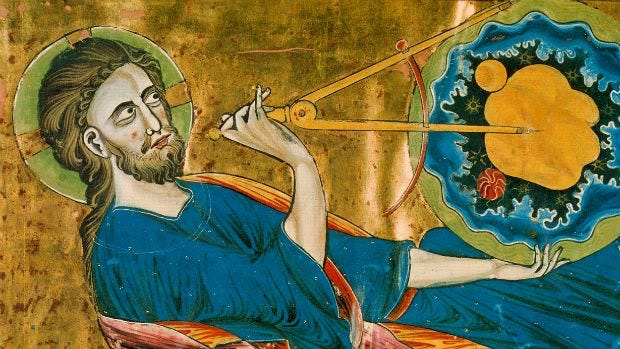

The idea was that music, math, and the cosmos were inextricably linked. The universe was deeply mathematical and God must himself be a divine geometer.

So, if the universe is one great musical composition, how do you live your life to be in tune with it?

One way is to make music that connects you to that divine order. But, as we’ll see, you can do it in the visual arts too — even in architecture...