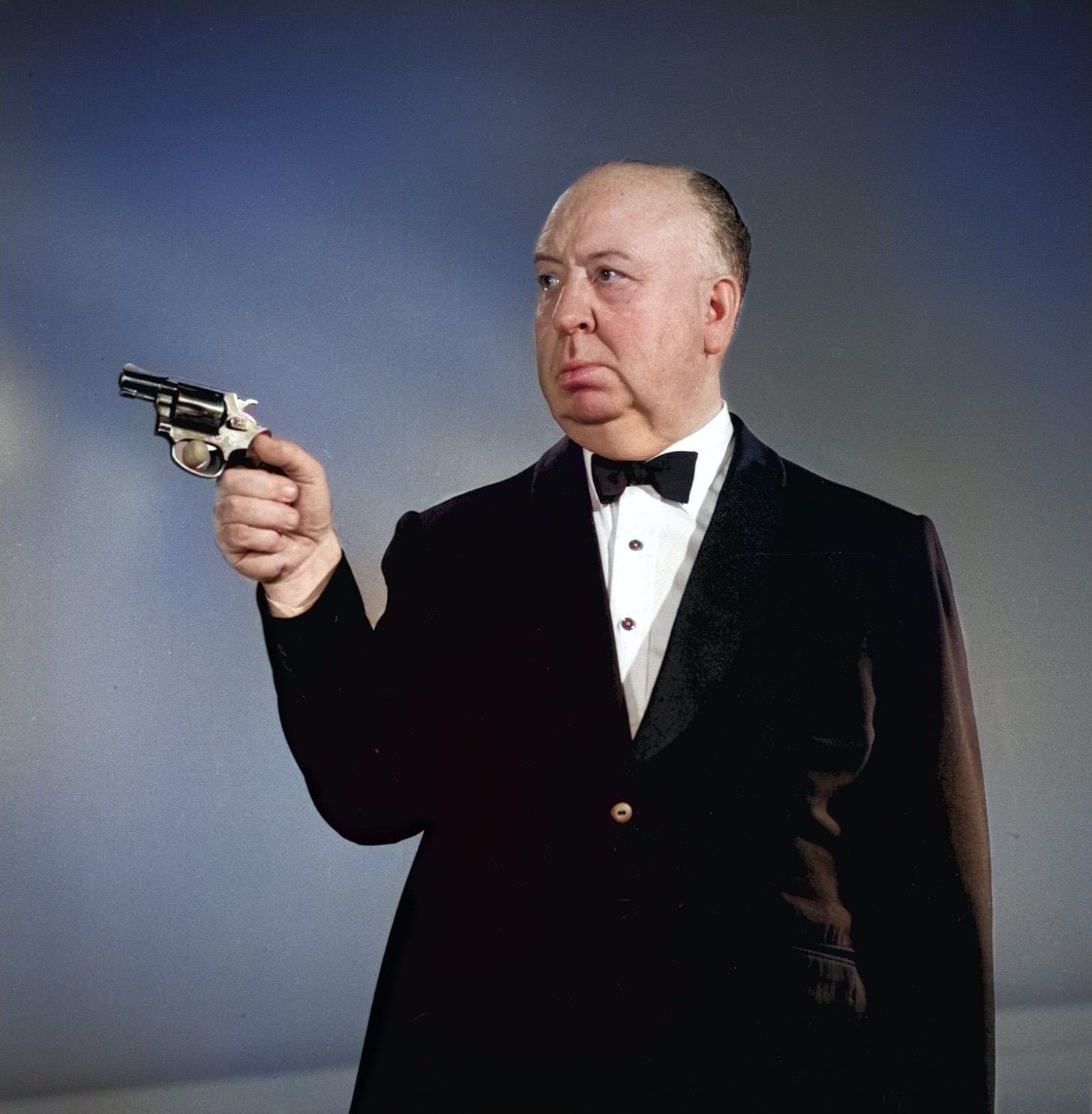

How to Tell A Story, According to Alfred Hitchcock

The making of a gripping tale...

What makes a film truly gripping?

Is it the dialogue? Perhaps the music? The special effects?

Alfred Hitchcock, the undisputed "Master of Suspense," built his legacy on this radical idea. He believed that cinema's power came from it being a visual medium, and therefore a director should aim to tell the story with as little dialogue as possible. As he put it: "It is to… drive one to make one work purely in the visual and not rely upon words at all."

But why does this matter today? In our age of binge-watching and CGI spectacles, Hitchcock's techniques remind us that great storytelling isn't about overwhelming the senses — it's about guiding them. By dissecting his principles: from establishing space to framing importance, evoking emotion through the body, and even transforming dialogue into visual poetry — we uncover how Hitchcock didn't just make movies, he brought us into different minds, worlds, emotions. And he did so without us even being aware of what was happening…

Reminder: you can get tons of useful members-only content and support our mission for a few dollars per month 👇

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Art of Space

Imagine standing alone in an endless field, the sky pressing down like a judgment. No words are needed to feel the isolation — it's baked into the image itself.

Hitchcock mastered this feeling by starting wide and drawing inward, a progression that orients the audience before plunging them into chaos. This isn't a lazy setup; it's psychological warfare. If you watch virtually any scene from any of his films, you'll notice that the shots often start zoomed out and then come closer as the scene progresses.

In North by Northwest (1959), Hitchcock tediously set the scene in the flat, open fields, depicting Cary Grant's Roger Thornhill waiting amid the dust and horizon. Then, when the plane arrives and starts shooting at him, this amplifies the drama as we know he has nowhere to find cover — no trees, no buildings, just endless exposure. Hitchcock doesn't explain Thornhill's vulnerability; he shows it, amplifying the terror through simple geography.

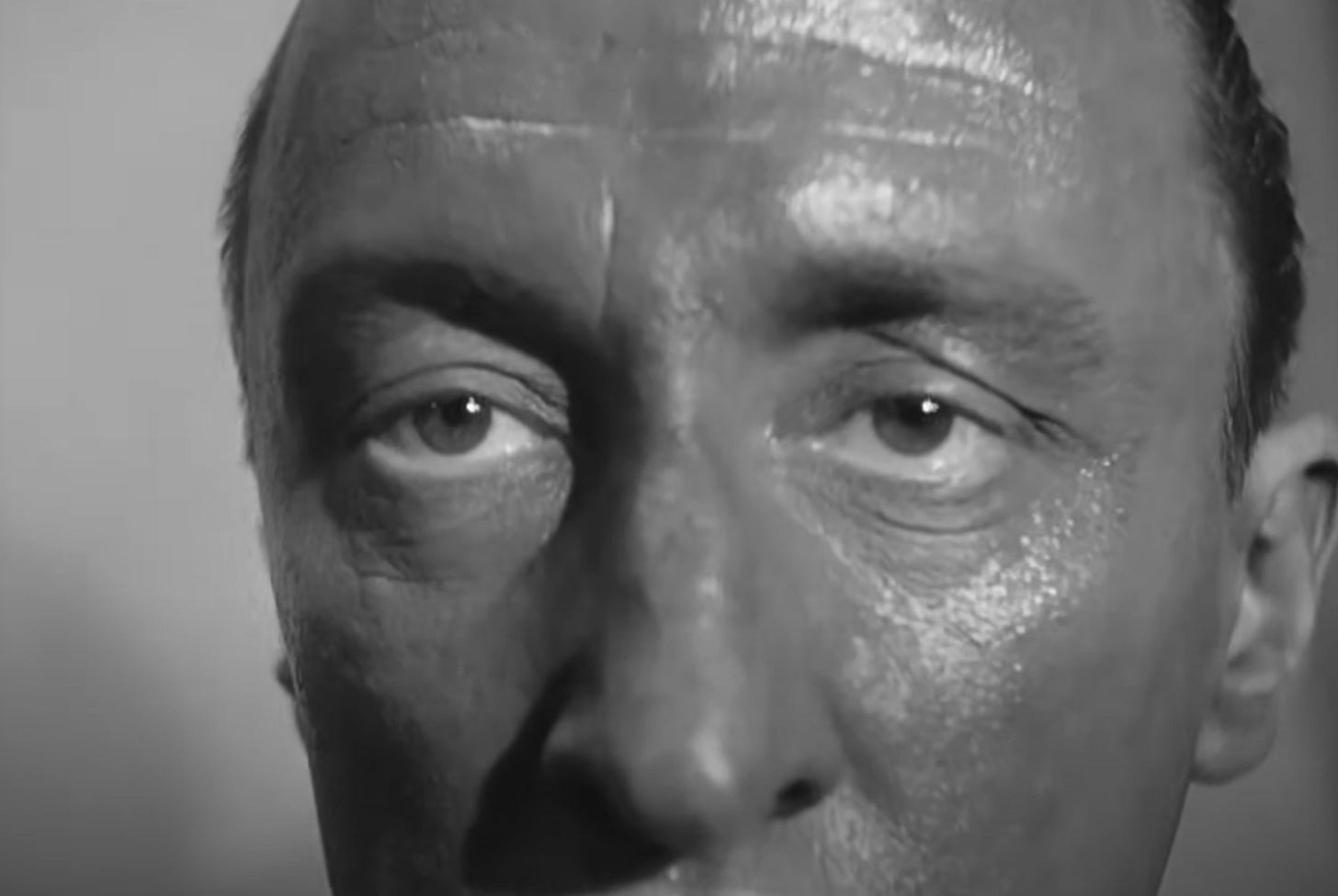

This technique echoes across his work, much like how ancient epics build worlds before unleashing heroes into them. Take his earlier British film Young and Innocent (1937), where a young woman searches a crowded hotel ballroom for a murderer, knowing only that he has a distinctive eye twitch. Hitchcock places the camera in the highest position above the hotel lounge, emphasizing how hopeless this task is amongst the packed ballroom. He then dolls the camera down through the dancers, up to the dance band, right to the drummer — a close up shot of the drummer until his eyes filled the screen, and then the eyes twitched...

The initial expanse underscores the needle-in-a-haystack odds, turning a boring search into a symphony of suspense. Without a single line of dialogue, Hitchcock conveys hopelessness, then hope, all through spatial storytelling. It's a lesson in patience: rush the close-up, and you lose the stakes.

Watch the Hands

Stories live or die by emotional connection to individuals on the screen — without it, even the grandest plot feels hollow. Hitchcock bridged this gap not with monologues, but with the body's raw sub-communication. Hands, in particular, became his shorthand for the characters’ inner secrets.

In thrillers rife with tension, hands betray what words and sometimes even the face conceal: steady grips for confidence, fidgeting for fear, locked and shaking for fury. Hands can contrast a character who is feeling confident with one who is nervous, or they can show how a character goes from feeling helpless to feeling angry.

Being Hitchcock, of course, hands are often associated with murder — and strangulation is easily the most common method in Hitchcock's films. The focus on hands emphasizes the power of one character and the helplessness of another.

Then afterwards, the hands frequently express guilt (washing them obsessively or hiding them away). Hitchcock liked close-ups of hands because they are "a very economical way to show emotion.” They were simple, cheap, and quick.

The Weight of an Image: Size as Significance

In storytelling, not all elements are equal — some whisper, others scream. Hitchcock knew this, insisting that the size of the image in the frame is proportional to its importance to the story at that time. Think long pauses on close up shots of certain objects here.

One application of this rule is how objects convey something of the character's personality (focus on a pair of shoes can suggest that one character is bold and brash while another is retiring and conservative), but often these shots let the audience know that an object is about to become important to the plot.

When these shots are done with great skill, we as audience members can know exactly what is happening without having to be told or guided through audio.

Consider Notorious (1946), where a cup of coffee becomes a harbinger of doom. Hitchcock isolates it frame after frame: carried across a room, set down with deliberate care. No one says "poison," but the visuals scream it. The cup is ominous, and we know for certain there is something dark brewing…