How to Rebuild From the Apocalypse

17th century Sicily shows that disasters are permanent only if you allow them to be...

The chipping away of our cultural heritage, both physical and rhetorical, has become a regular and saddening feature of life in the 21st century Western world.

Now imagine what it would be like if you lost all of it, all at once.

For the people of Sicily, this nightmare scenario actually happened, when in 1693, a cataclysmic earthquake reduced almost the entirety of the island’s south east to rubble. Thousands of lives, and thousands of years of cultural achievement were wiped out absolutely, without warning, and without a chance to save any of it.

For the survivors, it might as well have been the end of times itself.

But it was not. It was in fact the beginning of a golden age of Sicily.

For what happened next stands as a civilizational model of how best to respond to disaster, and how to truly ‘build back better’…

Reminder: You can get tons of members-only content dedicated to useful knowledge, and support our Mission at the same time for a few dollars per month 👇

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help you navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Great Catastrophe

“…But on that Sunday… at around nine o’ clock, all Sicily was rent asunder”

Antonio Mongitore, Istoria cronologica de' terremoti di Sicilia, 1743

By the 17th century Sicily stood at the head of a formidable and ancient history. From the indigenous Sicel tribes who gave the island her name, to the Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, Swabians, Aragonese, Spanish and beyond who had each ruled Sicily in turn, her culture had been over two millennia in the making.

Such was all that was lost on the 11th January 1693, when a catastrophic earthquake, as high as 7.3 in magnitude, razed the entire south eastern spur of Sicily, the Val di Noto, to the ground. At least 60,000 perished, and according to at least one report forwarded to the Spanish authorities in Madrid, the final death toll may have reached 93,000 victims. Sixty cities crumbled upon their foundations, including many of the region’s most ancient centers of civilization, including the capital of Noto itself. Of the 64 monasteries in the diocese of Syracuse, only 3 remained standing. No matter how bad you may think the situation is now, for the Sicilians of 1693, it was worse. Much worse.

Sicily, mourning and in shock, was in the direst of need. Not simply of immediate aid, but assurance that there was some kind, any kind, of future worth living on for. The temptation to simply write off their ancient homeland and move elsewhere would have been overwhelming.

Both the Sicilians and the Spanish Crown to which they were then subject now ultimately faced the same simple question. Can a civilization survive the destruction of its material roots? Is it possible to rebuild one? More importantly, how can we rebuild one better than before, while still connecting it organically to what came before?

Fortunately for the survivors, for Sicily, and for civilization itself, the Spanish Crown would bring far more than humanitarian supplies to the desperate Sicilians. They would bring a plan…

Restoring Order

A typical problem which plagues disaster relief today is that the instant the media coverage subsides, so too does the attention of the government.

Central Italy in particular is littered with communities ‘temporarily relocated’ in the wake of the many earthquakes which struck the country in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The story is always the same. At the time of the disaster, the political classes placate public anger by making extravagant promises to rebuild, which months and years down the line fail to materialize. Funds mysteriously disappear, tremendous resentment is fostered, and public confidence in the authorities’ capacity to handle future crises — or even care about them — dies by a thousand cuts.

The Spanish response to the Val di Noto earthquake, on the other hand, could not have been more different, and above all for one simple reason. The Spanish understood that in the face of a disaster of this scale, the legitimacy and credibility of the entire order was on the line, and that if they got this wrong, it could permanently rupture relations between Sicilians and the Crown.

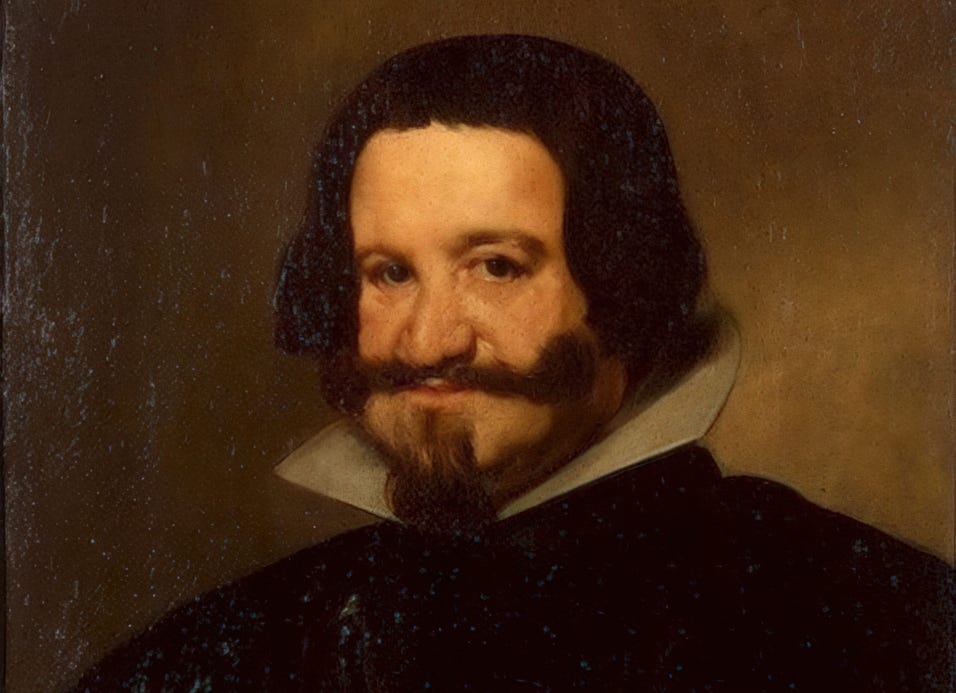

The first step of any effective response lies in choosing the right men to lead it, and the Viceroy of King Charles II in Sicily, Juan Francisco Pacheco, 4th Duke of Uceda, was diligent, organized, and possessed a clear sense of urgency. The Viceroy immediately established two emergency commissions, one to coordinate civilian aid, and another for the considerable population of clergy in the affected areas. This would be followed by his appointment of local nobleman Giuseppe Lanza, Duke of Camastra, as Vicar General, charging him with bearing immediate aid to Val di Noto, restoring law and order and overseeing the clearing of rubble.

Difficult decisions had to be taken continuously, and plans adapted. So profound was the instability triggered by the earthquake that Val di Noto was torn by aftershocks for two entire years, complicating the work of the Spanish reconstruction commissions. Nevertheless, that the Spanish had to deal with unpredictable conditions, while working with limited infrastructure and all the technological bottlenecks of the 17th century, did not prevent them from balancing multiple crises at once.

Crucially, however, the supreme virtue of the Spanish approach in Sicily was that it prioritized the long-term as much as the short-term. Reconstruction planning took place at the same time as relief operations, making it far more difficult for institutional inertia and bureaucratic obstruction to take hold. This, in an era where media coverage and political campaigning was non-existent, and thus there existed no cynical motive to ‘play to the cameras’, is only to be admired.

Thus, while food and shelter was provided to the traumatized Sicilians, and a measure of stability was restored to them, Lanza assembled a team to build them a future. It was a future that proved decisively that you can indeed rebuild civilization, and that you do not need to choose between beauty and efficiency…