How to Live Virtuously

And stop faking it

Throughout the ancient and medieval worlds, certain ideas about what makes a good person stood tall and firm. Among them, four virtues were seen as the cornerstones of a life well-lived: the so-called Cardinal or Classical Virtues.

They weren’t just abstract ideals; they were seen as practical, guiding principles for how to live rightly and fully. Self-control, wisdom, fairness, and courage — these weren’t merely lofty goals but fundamental laws to best navigate the complexities of life.

Over time, these virtues became a touchstone for many Western thinkers and educators who, relying on a Biblical worldview, believed that understanding and practicing them was key to living a meaningful and moral life. The Book of Wisdom states:

“And if anyone loves righteousness, her labors are virtues, for she teaches self-control and prudence, justice and courage; nothing in life is more profitable for mortals than these.”

All other virtues originate in these four virtues, and their cultivation results in a truly good and pious person. Further, the Western Tradition was founded on these virtues. If we are to understand our long tradition, then we must study moral action, steep ourselves in education, and — above all — pursue virtue.

Here's how to live a virtuous life by these four foundations of Western society...

Reminder: this is a teaser of our exclusive in-depth content.

To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Understanding Virtue

First, we must understand the concept of virtue. It is not a word used frequently in modern society, and has become antiquated in the popular understanding of morality. Today, the highest good and character of a person is not the pursuit of virtue, but rather the pursuit of wealth, power, or even more gravely, progression.

Perhaps the most egregious usage of virtue is “virtue-signaling;” that is, the appearance of virtue without any actual discipline. Modernity values the art of seeming but not being.

However, the ancients had a much higher view of virtue. The word has its roots in the Latin virtus. While it originated in the particular context of masculine pursuits, it has adopted a general meaning of excellence in all things.

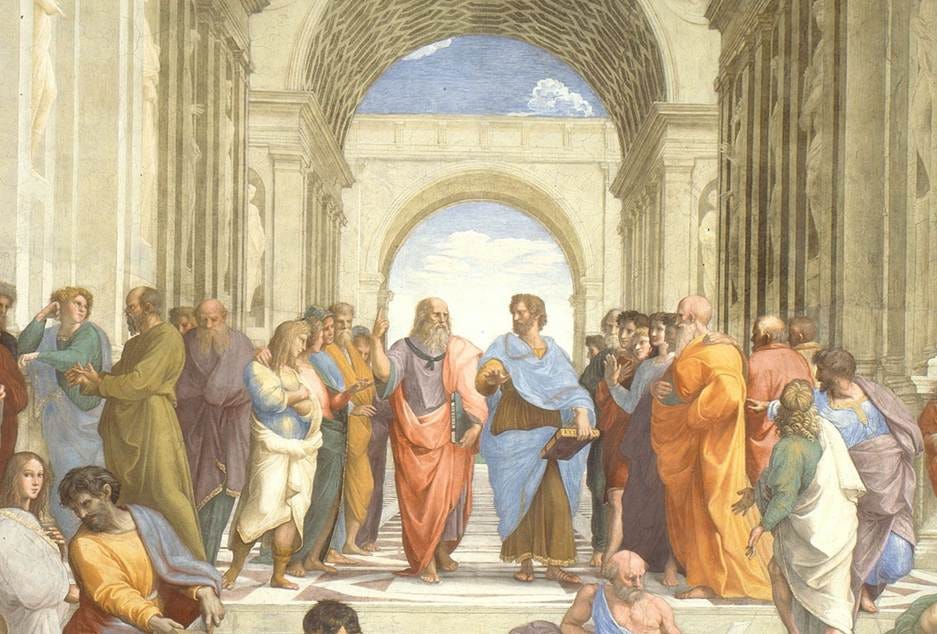

Beginning with the Greeks, especially Plato and Aristotle, the Greek form of the word became even more particular with regard to moral excellence. For Plato, virtue was that state of the mortal creature who, having a disposition toward that which is praiseworthy, is said to be good when possessing excellence in all things, particularly of the Good. For Aristotle, there is a similar meaning, but with a more particular emphasis on virtue’s relationship to vice, i.e. the mean between two vices.

Today, the “cultivation of virtue” is rarely mentioned. However, there is a growing body of like-minded people, inspired by our classical heritage and the love of the philosophical life, who now advocate for a renewed emphasis on the cultivation of wisdom and virtue.

However, before we can remake the culture, we must remake ourselves, and for that, we must first understand ourselves.

Three Parts of the Soul

In Platonic and Christian thought, the soul is that which makes man distinct from the irrational creatures. This soul is composed of three parts: intellect, spirit, and desire. There are various Greek words to describe these parts, but there are three generally used words: nour, thumos, and epithumia.

The nous is the rational, reasoning, or intellectualizing part of the soul. It is the chariot driver who leads the horses, desire and spiritedness as described by Plato. The rational part of the soul is not merely the analytical element by which man understands, but is that which governs the whole person through the intellect itself.

The thumos, called the chest by C. S. Lewis in the Abolition of Man, is that part of the soul which comprises the passions, spiritedness, and emotion. It is what drives us to glory and honor. It is also described as the irascible part of the soul, and it works together with the rational part to control the baser elements of the human person.

The epithumia, or the belly according to Lewis, is that which governs our appetites and desires, particularly, bodily pleasures. It is the irrational part of the soul most clearly connected with our physical existence as animal, desiring to eat, drink, and procreate.