Bread and Circuses: From the Roman Circus to Europe’s Modern Social and Entertainment Machine

Will Our Media Addiction Shape Our Political Future?

This piece by Dr. David Engels is part of multi-part series, Rome Reloaded, exploring the striking parallels between ancient Roman society and our own. Enjoy!

“The masses have long since thrown off their cares. The people who once bestowed military commands, consulships, legions, and everything else no longer involve themselves and now yearn with all their heart for only two things: bread and circuses.” (Juvenal, Satires 10.77–81)

Few expressions are as well-known as Juvenal’s panem et circenses, so much so that “bread and circuses” has become a standard shorthand for the subtler mechanisms of rule in the Roman Empire. Yet the time is long gone when this phrase could serve merely as a general warning. Today, the political and social function of entertainment and welfare has become more central than ever—chief among the preferred tools of political control. It is a system built on the deliberate sedation of civic engagement through basic material security and mass spectacle. But what do these analogies mean in concrete terms for a Western world immersed in nonstop fun culture and governed by a highly sophisticated welfare state?

The Ancient Circus Maximus: Entertainment as an Instrument of Rule

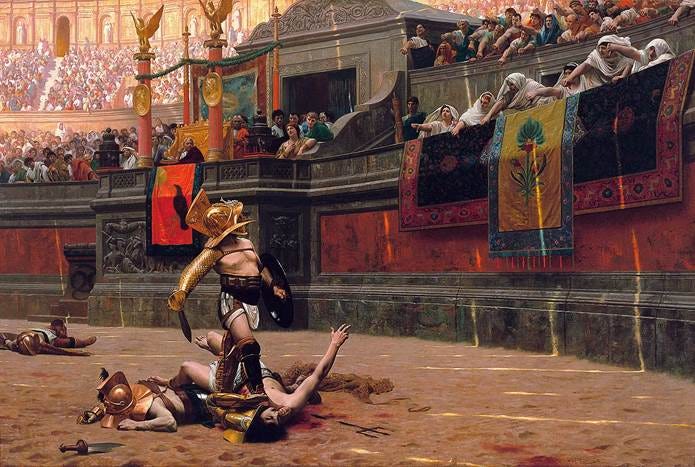

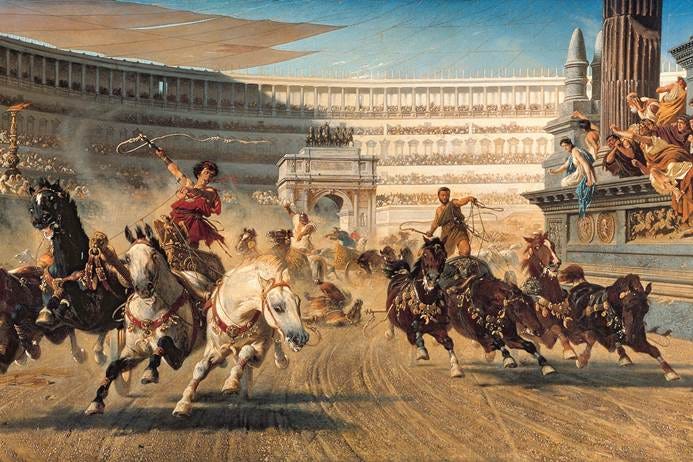

Let us look back. Gladiatorial games, chariot races, beast hunts, and theater performances had always been popular in the ancient world, often rooted in religious customs—think of the link between gladiatorial combat and Etruscan funerary rites, or the emergence of theater from the Dionysian cult. But by the 1st century BC, the days when such spectacles were understood as serious acts of worship—or even just as harmless diversion—were gone. All of them had taken on an overtly political function: not only, as in theater, through politicized content, but first and foremost through their systematic connection to political self-promotion and through the obvious sedation of the populace via cheap or even free entertainment on an enormous scale.

Whoever could entertain the people secured their favor; and eventually, the sheer expansion of these spectacles prevented any possibility of political maturity. Politicians like Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus staged lavish games at their own expense: entire menageries were brought in from Africa only to be slaughtered before cheering crowds in Rome, hundreds of gladiators died in carefully staged battles, and the most celebrated actors from across the world were summoned to perform great theatrical classics. The Circus Maximus, the Theater of Pompey, the Theater of Marcellus, and later the Colosseum became venues of ultimate power display and mass loyalty building.

At the same time, the Roman populace was pacified by the frumentationes—state-subsidized grain distributions. What began as an attempt to ensure the survival of the poorest during times of inflation and unreliable grain imports gradually morphed into a reliable tool for buying votes. Every ambitious politician tried to make the distributions cheaper and more generous. Under Gaius Gracchus, the plan was put forward to introduce full regular provisioning for broad segments of the population—a measure Cicero criticized sharply:

“Gaius Gracchus proposed a law on the distribution of grain. The people received it with great joy: food was now offered to them freely and in abundance, without any work. But the better citizens rejected the law, believing it would empty the treasury and habituate the people to idleness.” (Cicero, Sext. 103)

Under Clodius, grain was finally distributed entirely free of charge. It consumed one-fifth of the state treasury and was claimed by roughly 320,000 people—half the urban population of Rome.

This dual function of “bread and circuses”—material security and emotional diversion—ultimately rendered the people politically superfluous. A republic once built on active citizens turned into an arena of passive consumers. Political debate faded as attention shifted to the next spectacle or payout.

The Modern Arena: Stadium, Screen, Welfare State

Do we even need to point out that a similar arrangement has taken shape in the modern West? While democracy is formally preserved, public interest has shifted more and more toward virtual entertainment and competitive sports.

Baseball and soccer have become a Western myths: Millions follow the games, identify with teams, and channel emotions that no longer have any outlet in political life. And while stadium sports still allow for some collective enthusiasm—always a risky moment when people might rediscover their own strength—the most advanced form of the modern circus, total immersion in virtual gaming worlds, has eliminated that danger altogether. The feeling of being part of a crowd has been replaced by the solitude of the screen or VR headset: where ancient crowds could still display their discontent and pressure emperors to change course, today the only things that matter are algorithms and click-rates.

Reminder: you can get tons of useful members-only content and support our mission for a few dollars per month 👇

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Layered onto this is a vast welfare architecture: child benefits, basic incomes, housing subsidies, transfer payments. A cradle-to-grave safety net has emerged that calms economic anxiety but also creates a new form of dependency—and will almost certainly, even in the supposedly “free” democracies of the West, be tied to a kind of social-credit system. Citizens—first stripped of work opportunities by billionaire-driven crony capitalism and then by artificial intelligence, reduced to mere consumers—are then pacified by a guaranteed income linked to political compliance.

Is it any wonder that active investment in public life—election participation, party membership, civic associations—has been declining for decades? Only now and then, when public sentiment has been artificially whipped up and the stakes seem high (usually not around values or long-term projects, but around distributional conflicts), do we see flashes of civic engagement—consider the recent U.S. elections as an example. But we can expect this, too, to diminish as the new post-democratic order solidifies.

Meanwhile, media consumption, entertainment addiction, and sports fanaticism rise. The “citizen” gives way to the “entertainment consumer.” The state itself is increasingly perceived not as a political project but as a service provider—a “nanny” that manages entitlements.

The consequences are profound. As in late Rome, modern citizens lose the ability—and eventually even the desire—to understand the political community as their sphere of action. When politics ceases to involve decision-making and becomes merely the distribution of goods, and when the political class reveals itself largely corrupt or incompetent, consumption replaces civic participation, partly out of contempt, partly out of infantilization.

The loss is twofold. First, collective judgment is systematically weakened—indeed corrupted. Instead of weighing arguments, many follow media staging, symbolic spectacles, emotional atmospheres, or the appeals of whoever pays the most. Second, the political class is freed from the need to serve the people when the people can simply be purchased: maintain or increase welfare payouts, provide emotionally charged mega-events, and fundamental questions will stay safely ignored. As long as the worst catastrophe in the news is immediately followed by trivial sports updates, citizens remain reassured—just like those Romans who, after their city fell to the barbarians, worried mainly whether the next circus games would still take place.

The Future

What does this imply for our future? If we assume that the evolution of the late Roman Republic foreshadows the trajectory of our own late-stage Western civilization, it is worth considering what happened to panem et circenses under Augustus.

By the time of the first emperor, the system was fully developed: registered citizens received monthly grain rations, and later olive oil, meat, and sometimes even money. Yet this outcome was not predetermined. Caesar had initially tried to promote greater civic responsibility by cutting the list of grain recipients in half—one of several reforms that contributed to the intense hostility culminating in his assassination. Augustus, though highly conservative in most areas, learned from Caesar’s failure. In one of his writings, he admitted:

“I attempted to abolish the public grain distributions permanently, because the secure expectation of these handouts removes much labor from agriculture. But I did not carry the measure through, convinced that after my death, the bidding for popular favor would sooner or later bring back this abuse.”

(Suetonius, Aug. 42.4)

Accordingly, he restored the names Caesar had struck from the rolls, returning the numbers to their previous heights to secure the people’s favor. And he mastered the symbolic resources of the Roman state, inundating the populace with an endless stream of spectacles, meticulously catalogued in his public accounts. Having learned from his adoptive father’s mistakes, Augustus made a point of attending the most important games in person:

“He used to watch the circus games from the box of one of his friends or freedmen, sometimes reclining with his wife and children. … And while he watched the games, he did nothing else, either to prevent complaints—since he remembered that critics had once accused Caesar of reading and even answering letters during the games—or because he genuinely delighted in them.” (Suetonius, Aug. 45.1–3)

We may expect something similar for the West’s future. Even an “Augustan” reform era would likely neither achieve—nor desire—true civic maturity. The Roman Republic did not fall to Caesar alone, but to its own civilizational exhaustion. Its institutions remained in form but were hollow. Citizens accustomed to handouts and entertainment lost all sense of freedom, responsibility, and duty, and no longer had the strength to rebuild a healthy system—or to sacrifice themselves for it. Even the most idealistic politicians realized they could not win the masses through responsibility, only through spectacle and provision. No wonder the best and most principled minds of the early Empire recoiled from politics in disgust.

The same exhaustion is taking shape in the modern West. Parliaments are already losing significance; decisions are drafted technocratically, implemented post-democratically, and then “explained” by the media. The citizen watches, feels a vague unease, yet remains largely passive. Sports and online games are more exciting than any parliamentary debate; the next holiday more important than the next election.

The system is not yet fully developed, and political power remains unstable—so we should expect crises, surprises, and unrest reminiscent of the late Republic, as already visible in France and the United States. But once the coming era of “Caesars” has passed and a new quasi-imperial administrative order has settled in, the citizen will likely relapse into his partly self-inflicted immaturity, preferring “events” to ethics—until perhaps, in a few centuries (or perhaps only decades), the next great migration shakes him from his sweet dream of sedation.