Blueprint for Freedom: the U.S. Constitution

Hope made manifest in a document...

The Constitution of the United States of America stands as the world’s oldest and shortest written national constitution still in use.

Containing just 4,400 words, this deceptively concise document has outlasted empires, inspired revolutions, and shaped nearly every democratic charter that followed.

However, behind its simplicity lies a story of secrecy, compromise, and human imperfection and the story of how 39 men forged the political foundation of an entire nation.

A Summer of Secrecy

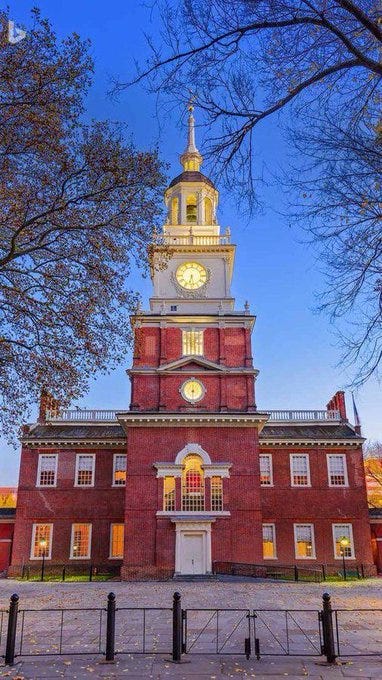

The summer of 1787 was sweltering in Philadelphia. For nearly 100 days, delegates gathered inside Independence Hall to draft a new government that could succeed where the Articles of Confederation had failed.

They worked in total secrecy: the windows were nailed shut to prevent eavesdropping, and guards stood watch outside.

This decision for privacy wasn’t taken lightly.

The American Revolution had just ended, and the new republic was fragile. Every word debated inside that chamber had the potential to divide states or undo the hard-won independence they had just secured.

James Madison, often called the “Father of the Constitution,” recorded the proceedings in meticulous detail, but his notes were not published until after his death.

The framers understood that to design a government for the ages, they first needed the freedom to argue without the world looking in.

A Republic, Not a Democracy

One of the Constitution’s most misunderstood features is what it actually establishes. Nowhere in the document does the word “democracy” appear. The framers feared that direct democracy — government by simple majority — could lead to mob rule and instability.

Instead, they built a republic, in which the people’s will is expressed through representatives, constrained by checks, balances, and laws. This distinction reflected lessons drawn from history.

The collapse of ancient democracies such as Athens and the turbulent experience of state governments under the Articles convinced the delegates that liberty must be balanced with structure.

The Constitution’s architecture, separation of powers, federalism, and a system of representation, was their solution to that enduring tension.

The Men Behind the Manuscript

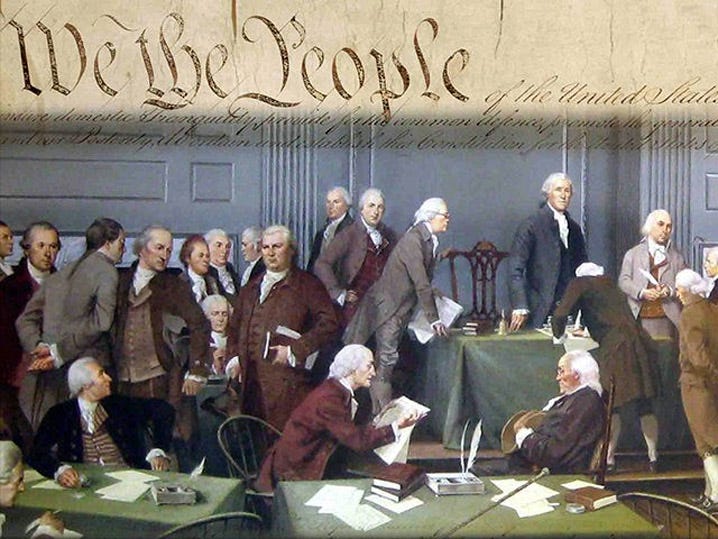

Fifty-five delegates attended the Constitutional Convention, but only thirty-nine ultimately signed the finished document. Many of the most famous figures of the American Revolution were absent.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were serving as ministers abroad, Jefferson in Paris and Adams in London. Patrick Henry refused to attend altogether, declaring, “I smell a rat.”

Yet the group that remained represented a wide cross-section of the new republic: lawyers, merchants, soldiers, and planters from twelve of the thirteen states. Rhode Island boycotted the convention entirely, fearing a loss of autonomy.

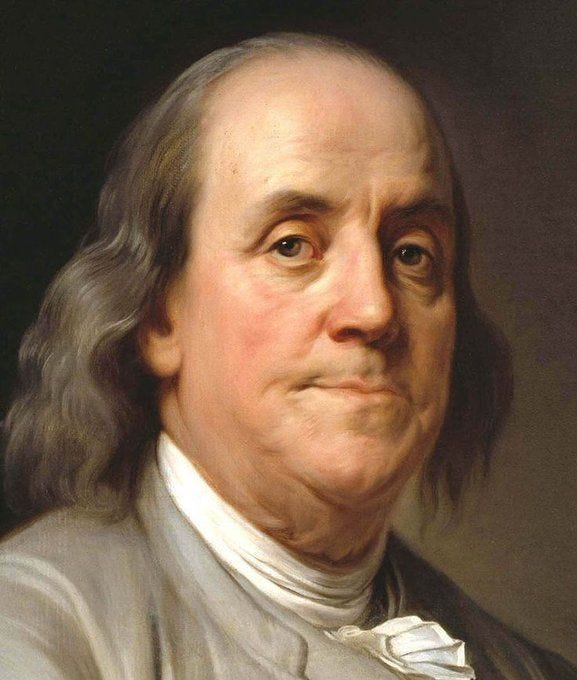

The average age of the delegates was just 42, though their intellectual and political achievements far exceeded their years. At 81, Benjamin Franklin was the oldest among them. By the time of the signing, he was so frail he needed assistance to put pen to paper.

As witnesses later recalled, tears rolled down his cheeks — not of sorrow, but of relief and gratitude that consensus had finally been reached. At the other end of the age spectrum stood Jonathan Dayton of New Jersey, just 26 years old.

A Revolutionary War veteran, Dayton would later serve as Speaker of the House and lend his name to the city of Dayton, Ohio. The Constitution’s signers thus spanned generations, from the youthful to the elderly, united by the ambition to create something that would outlive them all.

Language Changes

Even the most monumental works of history are still human creations. The Constitution is no exception.

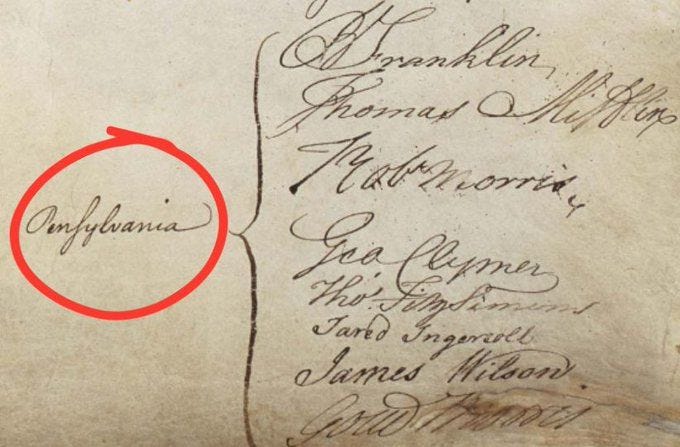

In a small but telling detail, the original spelling of the state of Pennsylvania was different in those days: “Pensylvania,” with one “n.”

The document itself was handwritten by Jacob Shallus, an assistant clerk for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. For his careful penmanship, Shallus was paid $30 — roughly $726 in today’s money. Using quill and ink, he transcribed the framers’ final revisions onto parchment made from treated animal skin.

The Constitution Expands

The original Constitution was a framework — remarkable in its design but incomplete in its protections. Many states initially refused to ratify it without explicit guarantees of individual rights…