Between the Arena and the Battlefield

Sport as a Facsimile of War

The human spirit is marked by a restless striving for excellence, a desire for honor, and a natural inclination toward competition in the public arena – whether it be the sporting or the battle field. This relationship between sport and warfare is not accidental but essential.

Both sport and warfare arise from the same impulses of competition, courage, and the pursuit of glory. Sport, in its noblest form, is a facsimile of warfare – an imitation of combat that channels martial prowess into a controlled and constructive arena free from the penalties of death.

But like all human endeavors, it becomes a vice when taken into excess. When sport ceases to cultivate virtue and instead becomes a narcotic spectacle, it risks becoming what Juvenal derided as “panem et circenses” – or bread and circuses – an opiate that distracts men from their civic duties.

Sport as a Facsimile of Warfare

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle clearly articulated the foundational ethical principle that “virtue is in the mean”, and that human passions and activity, though potentially destructive when unrestrained, can be ordered toward the good when governed by reason. Sport exemplifies this principle as it provides a regulated outlet for aggression and competition – impulses that, if left unrestrained, can precipitate civil unrest and violence.

In the arena, these impulses are disciplined by rules, enforced by referees, and performed within strict boundaries, transforming destructive tendencies into displays of skill and endurance. Sport, like war, is a theatre of activity where courage, endurance, and discipline are tested. Yet unlike war, its stakes are not life and death but recognition, honor, and praise.

The martial character of sport is evident in its elaborate organization and rich symbolism. Teams are arranged like armies, with coaches as generals, players as units, and strategies described in tactical terms. Uniforms, anthems, and ceremonial openings evoke the solemnity of military ritual. International competitions, in particular, resemble symbolic battles between nations, where flags, medals, and trophies replace the traditional spoils of war. Thus, sport functions as a controlled facsimile of war that imitates the structure and spirit of combat while mitigating its destructive consequences.

Cultivating Character Through Competition

Properly ordered, sport cultivates virtues essential both to the individual and to the polity. It promotes physical health, discipline, teamwork, and resilience. Furthermore, it cultivates – primarily within children – the virtues of perseverance in adversity and magnanimity in victory.

The Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero recognized the formative power of physical exercise in children, writing in his Tusculan Disputations that “It is exercise alone that supports the spirits, and keeps the mind in vigor”. This principle which served as the basis for Roman pedagogy was not exclusive to the Roman Republic alone, but echoed the even more ancient example of the Greeks. The celebrated warrior and philosopher Xenophon wrote in his Memorabilia that “Those who do not train the body cannot perform the functions proper to the body, so those who do not train the soul cannot perform the functions of the soul”. Both Cicero and Xenophon maintained the ancient wisdom that strong citizens are those of strong bodies and strong minds, and strong citizens make strong states.

This perspective was further refined by the Scholastics of the Middle Ages. In his Summa Theologiae, St Thomas Aquinas praises the virtue of eutrapelia (playfulness or recreation) as the mean between excessive seriousness and frivolity. Sport, Aquinas argued, is a form of leisure that refreshes the soul, prepares man for higher pursuits, and considered it a remedy to hagiosthenia or spiritual fatigue. He concluded that sport is a good insofar as it is proportionate, ordered to the cultivation of virtue, and reflective of man’s natural desire for excellence. Yet it becomes vicious and disordered when it degenerates into mere entertainment and divorced from the higher ends of civic responsibility and moral formation.

The Political Power of Spectacle

“Man is by nature a political animal”, and to this end, sport also fulfils man’s natural inclination towards community. Supporters of a team form a kind of civic body, united by chants, colors, and symbols where victories and defeats are shared collectively, ultimately strengthening tangible bonds of identity and solidarity – a spectacle which is most evident in international events such as the Olympics.

However, this can degenerate into hostility when exercised disproportionately, as communal spirit degenerates into tribalism, and support is translated into justification for tangible conflict. In these instances, the very same passion that unites supporters can also be the very same passion that incites violence against rivals, which removes the proverbial veil, giving the public a glimpse of the real violence that sport aims to replicate – or rather domesticate.

Pleasure as a Path to Passivity

St Augustine of Hippo recognized that the martial spirit displayed in the Roman games, when rightly ordered, was necessary in serving the common good. However, in his magnum opus, the City of God, he warned of the dangers of confusing symbolic combat with true virtue, “For the shows, when they are frequented, draw men away from serious occupations and useful business, and lead them to vain and wicked things”. As with many Romans of his time, Augustine emphasized the challenge lies in ensuring that sport remains a school of discipline rather than a theatre of distraction.

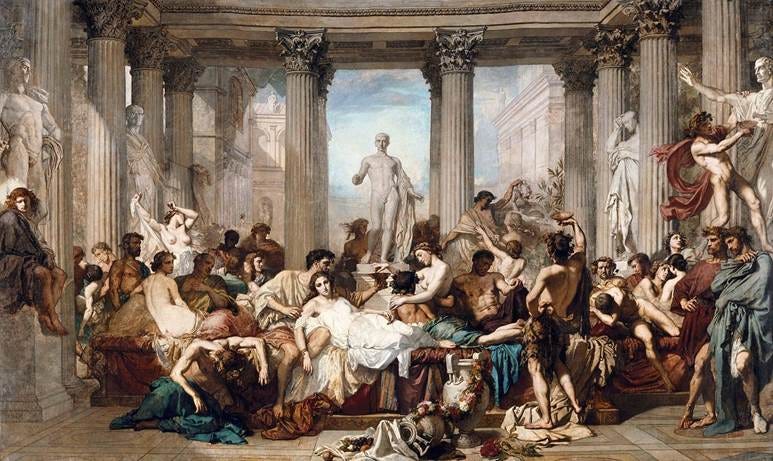

Following this, St Thomas Aquinas warned of the dangers of disordered loves as part of his wider exploration of the ordo caritatis (order of charity). When inordinate attachments to lesser goods – such as sport and entertainment – eclipses or rather distracts from greater goods, these inevitably engender effeminacy within the individual and the collective, making them both spiritually and morally weak as the body adjusts itself to the operations of the soul.

From Discipline to Decay

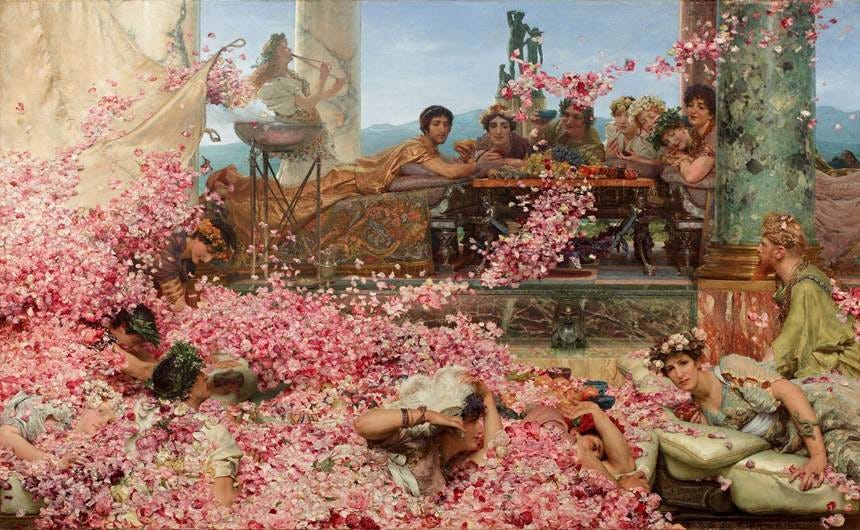

When sport becomes an end in itself, detached from the cultivation of virtue, it risks degenerating into a pointless spectacle. In his time, Augustine lamented the Roman obsession with gladiatorial games, where citizens, “drunk with the madness of the shows”, abandoned their civic responsibilities and “anxiously hoped for just two things: bread and circuses”.

In the modern age, the commercialization of sport reduces athletes to commodities and supporters into consumers. The relentless cycle of games, commentary, and gambling fosters a culture of distraction, where civic engagement is replaced by passive entertainment, and young men are diverted from their dual end towards a perpetual state of arrested development. At times, it risks subjugating and domesticating, and rather than cultivating virtue and excellence, it cultivates vice, encourages passivity, and normalizes complacency.

Echoes of an Empire

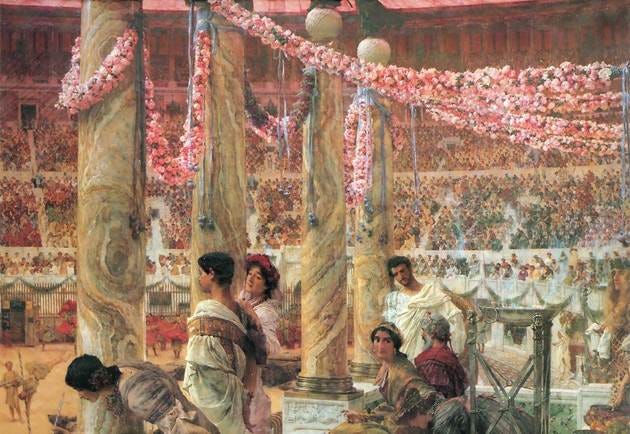

The decline and fall of the Roman Empire illustrates the dangers of excessive devotion to spectacle. As political corruption deepened in the third and fourth centuries, the populace turned increasingly to gladiatorial combat and chariot racing for solace. These entertainments provided a superficial sense of unity while masking the decay of civic virtue and impending collapse of society.

Writing in the aftermath of Rome’s sack by the Visigoths, Augustine argued that “the destruction of the city was the punishment of its vices”, as he believed that the Romans’ inordinate attachment to the games distracted them from their civic duties, and in doing so, hastened its moral collapse.

From its foundations, the strength of Rome was forged “through care and force of discipline” as Vegetius observed. Citizens, hardened by manual labor and bound by duty, sought glory not in idle spectacles but in the defense of their fatherland whether in the political arena or on the battlefield. Yet as the empire expanded and the corrupting influence of wealth crept in, the spirit of the Roman people turned from arms to amusements, and rather than turning to the temple, they turned to the circus. They raised men who lived for the sensationalism of combat – the facsimile of war – rather than war itself, and until they were conquered by a people who still lived by the sword.

The Cost of Complacency

So too in our own age, men surrender their strength to diversions. The contests of athletes, though of no consequence to the fate of nations, consume the passions once reserved for civic duty and sacrifice. As in Rome, rulers find in such entertainments a ready means of pacification, for a people absorbed in games is easily governed, content to cheer from the stands while others shape their destiny.

The lesson of history is clear: when a society exalts performative feats and spectacles above discipline, it sows the seeds for its own subjugation as man places himself in invisible shackles.

Rome, the greatest of empires, was not defeated by her enemies, but by the weakness and effeminacy bred within her walls, and modern man, if he persists in this course of action, may follow her example.

Step by step they were led to things which dispose to vice, the lounge, the bath, the elegant banquet – all this in their ignorance they called civilization, when it was but a part of their servitude. – Publius Cornelius Tacitus (Agricola)

I was born in Rome and I confirm.