Between Existential Fatigue and the Dogma of Equality

The West’s demographic decline as reflected in Rome

This piece by Dr. David Engels is part of multi-part series, Rome Reloaded, exploring the striking parallels between ancient Roman society and our own. Enjoy!

The West is aging and shrinking, and so is its future.

The symptoms are well known: declining birth rates, growing childlessness, aging societies, collapsing pension systems. But this change is not simply a random biological or economic phenomenon but rather the expression of a cultural crisis, a crisis that once shook an empire: late Republican Rome.

A comparison of the developments at that time with the situation in Europe today reveals striking parallels and cautionary insights.

Reminder: To get our members-only content every week and support our mission, upgrade to a paid subscription for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Two full-length, new articles every single week

Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Loss of Children

In the Roman world of the 1st century BC, the birth rate, at least among the upper classes, became a pressing and much-discussed problem. As early as the 2nd century BC, Polybius lamented the declining number of children in the Hellenistic heartlands and attributed it to excessive individualism:

"In our own time (end of the 2nd century BC), the whole of Greece has been afflicted by childlessness and a general decline in population, as a result of which the cities have become desolate and the land barren, even though we have had neither long wars nor epidemics [...]. Since people had degenerated into arrogance, greed, and indifference, they neither married nor, if they did marry, wanted to raise their children — at most one or two, so that they could leave them wealth and raise them in luxury — this evil quickly gained the upper hand without anyone really noticing."

In Rome in particular, this development would become a problem not only economically but also politically. Whether it was the recruitment of citizen soldiers, who were privileged members of the middle and upper income classes, the increasingly asymmetrical relationship between locals and immigrants, or the destabilization of the increasingly childless families of the political nobility: The demographic decline emerged as a key accelerant of the Republic’s unravelling.

No wonder that Augustus, of all people, enacted laws to counteract this: The leges Iuliae and the lex Papia Poppaea made divorce more difficult, criminalized adultery, and obliged senators to marry and have children — otherwise they faced sanctions. Augustus is said to have explained in one of his speeches:

"If you like this lonely life, it is not because you would live without women; hardly any of you eat or sleep alone: what you desire is the free satisfaction of all your desires and vices. [...]. You can see for yourselves how much your numbers exceed those of married citizens, even though you should have given us at least as many children as there are of you. [...] It would be a crime, a disgrace, if our people were to perish, if the name of the Romans were to end with us, if our city were to be left to foreigners, such as the Greeks or barbarians. Should it come to pass that we free our slaves only to keep the citizenry as large as possible, and grant citizenship to our allies in order to increase our population, while you, Romans of Roman origin, who proudly count the Marcii, Fabii, Quintii, Valerii, Julii among your ancestors, obviously want to let both your people and your name perish?"

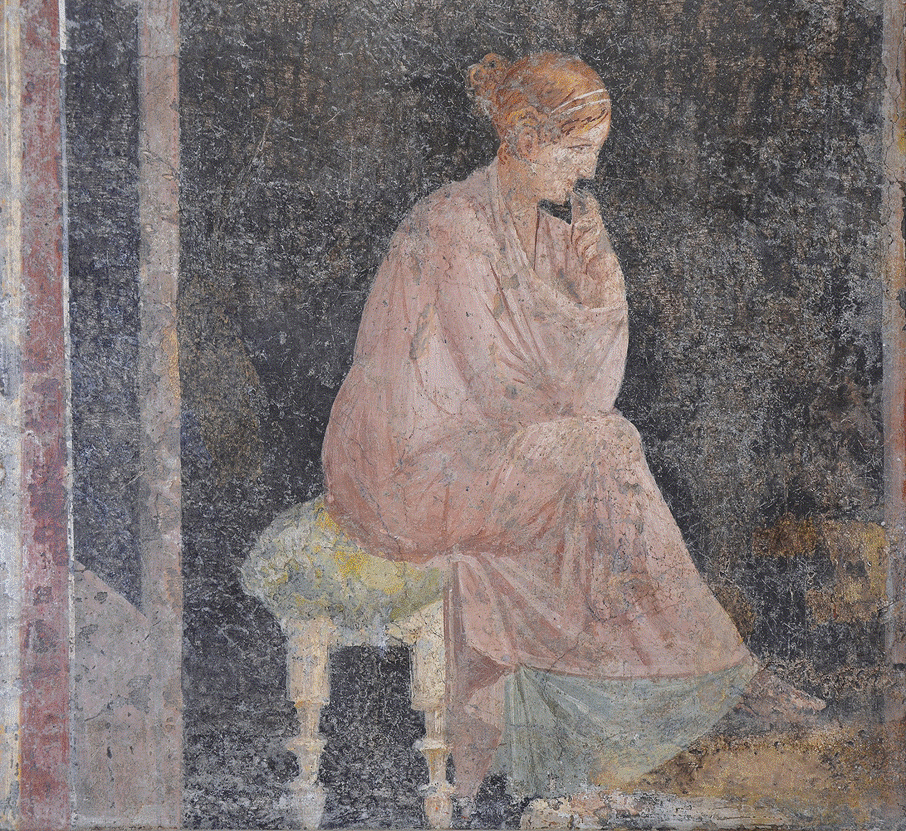

But cultural change was stronger: even in the imperial period, marriage was increasingly seen as an economic and social burden. Contemporary authors such as Suetonius or Tacitus therefore reported numerous cases of Roman wives who preferred to divorce their husbands rather than submit to motherhood. The matrona Romana lost her status, and children were considered an obstacle to personal ambition. Many members of the upper classes preferred to live in comfortable childlessness, while the poorer classes had more children but exerted little social influence.

The Breakdown of the Family

The West is currently experiencing a similar development. Despite generous family support, parental allowances, the expansion of childcare facilities, and gender equality measures, the birth rate remains well below the replacement level. In large parts of Western Europe, it stands at 1.4 children per woman—too few to maintain a stable society. Even in countries such as Hungary, which has invested heavily in increasing its disastrous birth rate, positive results have ultimately failed to materialize: the desire for “self-fulfillment” is too strong here as well, because children are now regarded universally as a personal lifestyle choice, no longer as a social given. The idea that there could be a duty to pass on life and love has largely disappeared.

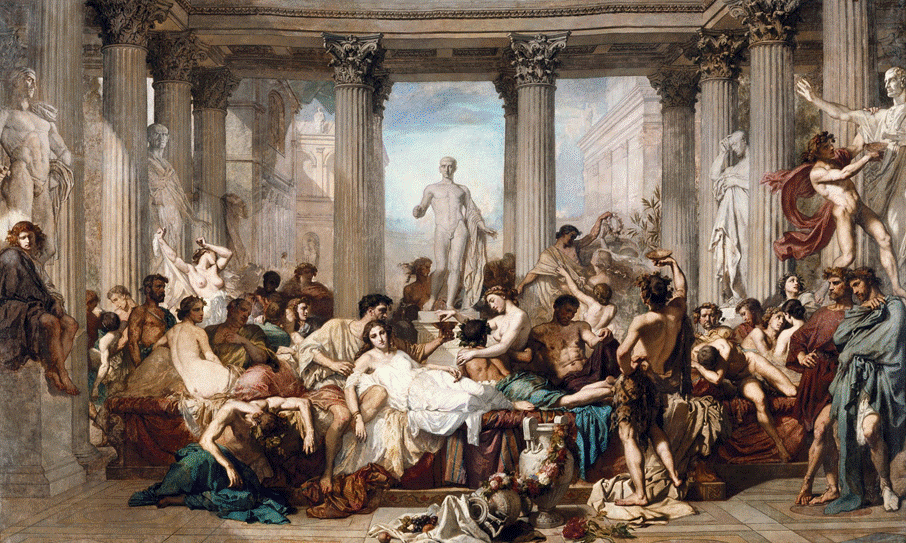

What are the reasons for this development? In Rome, the familia was once the backbone of society and included not only father, mother, and children, but also slaves, clients, and relatives. The pater familias had absolute authority, his role combining power with responsibility. However, with the advance of Greek philosophy, individualistic lifestyles, and growing social mobility, these structures gradually dissolved. Divorces became common, marriages temporary, sexual availability ubiquitous, and the authority of the father a vague memory of an archaic past. Pompey, Cicero, and Caesar all divorced for political reasons, and many senators changed spouses several times, whether for erotic, emotional, or strictly political reasons. The family became a community of convenience rather than a lifelong commitment.

In the West, a similar picture has emerged since the 1960s at the latest, even though divorce had of course been a much-discussed topic since the 19th century. Since then, the traditional nuclear family has continued to lose importance; patchwork families, childless partnerships, people living alone, and “digital nomads” now dominate the picture. Marriage is being stripped of its legal and cultural model, parenthood is becoming a private decision, and the introduction of same-sex partnerships and “marriage for all” is ultimately depriving marriage of its natural legal basis. What once bound generations together is now seen as a risk, a restriction, a temporary option. The family as a fundamental social institution is in a state of progressive erosion.

Privacy and Equality

A central feature of both eras is thus the retreat into private life. In Rome in the late 1st century BC, the republican virtues — duty, self-sacrifice, service to the res publica — lost their appeal; instead, Epicureanism and skepticism flourished: Philosophy advised turning away from the world, toward otium cum dignitate. The Roman elite withdrew to their villas, discussing ethics or art, but caring little about the future of the state, which increasingly seemed synonymous with populism, civil war, demagoguery, shady financial dealings, and dirty hands.

The West is also experiencing such a depoliticization: political engagement is declining, trust in institutions is crumbling, interest in history, responsibility, and collective identity is waning; instead, personal optimization strategies, wellness, self-realization, and mobility dominate. Children, family and commitment have come to be regarded as burdens. The conviction that one's own life could be part of a larger whole is fading, because no one wants to identify with that very concrete “larger whole” that the late civilizational state reveals itself to be. In both Rome and the West, the promise of freedom from obligation has thus paradoxically bred a loss of freedom to shape the public sphere.

Added to this is a certain cult of equality between the sexes. The late Roman Republic did not, of course, know complete equality, but there was a growing emancipatory discourse through which gender-specific role models lost their binding force: Women enjoyed increasing economic independence, spoke in court, involved themselves in their husbands' political decisions, left the upbringing of children to slaves, and played an increasingly independent sexual role, as Roman poetry of the time describes in detail — a development that moralists blamed as a major factor in the decline of the classical family ideal.

Today, we are experiencing a similar phenomenon: an exaggerated belief in equality that not only dissolves any functional or biological differences between men and women, but also makes them politically suspect. The differences between the sexes, the specific roles of mother and father, the importance of generational succession and natural dependencies — all of this is relativized, denied or translated into a purely economic and financial quantification. Equality is no longer understood as a political and moral ideal, but as an anthropological fiction: all people are equal, always, everywhere, in everything. The consequence is an anthropology of interchangeability — human beings as genderless and isolated individuals.

The Instrumentalization of Life

Anyone who talks about declining birth rates in a highly sexualized world is also talking about contraception and abortion — and here it must be emphasized that this is more a matter of personal willingness to act than of concrete technology. In ancient times, unwanted newborns were largely abandoned; this was socially accepted, even if it was repeatedly criticized by philosophers.

Even more unanimous was the acceptance of suicide, which was idealized as a dignified alternative to a life and death in poverty or illness. Since late Republican Rome, however, life seems to have become even more functional than before: the breakdown of the family, extreme social polarization, and dehumanized life in a gigantic metropolis brought with it even greater cold-heartedness and a wide variety of techniques for terminating unwanted life, as illustrated by Iuncus:

“But if, for example, an elderly man should also be struck by poverty, then he himself would probably wish to be allowed to leave this life for good because of the difficulties he faces: because he cannot find anyone to guide him, no one to feed him, (because he) does not have enough clothes, no roof (over his head), no food, and possibly no one to fetch water for him. Those who see him, even if they call themselves friends and fellow residents, consider him a nuisance and a painful, pitiful, and (all too) long sight.”

No wonder that it was precisely at that time that the Jewish (and later Christian) message of the unconditional preservation of life found such great resonance as the only honest answer to human misery.

In the modern West, we are also seeing a growing functionalization of life: reproductive medicine, prenatal diagnostics, the euthanasia debate, gender selection, genetics — all of this suggests that life should be plannable, selectable, and optimizable, and that humans see themselves not as part of life, but rather as masters of life, while respect for life — for the weak, the unplanned, the different — is disappearing dramatically.

Societies without a future

A society that no longer has children, that devalues the family, that functionalizes life and turns equality into interchangeability, robs itself of its future. During the imperial era, Rome attempted to compensate for its demographic problems by restricting immigration, implementing integration measures and, above all, promoting marriage and childbirth through massive propaganda and legal incentives, albeit with only moderate success. Europe, on the other hand, continues to focus entirely on individualism, immigration, and multiculturalism, without recognizing that this may correct statistical figures but only exacerbates the underlying cultural problem.

For the demographic problem is not technical, but spiritual: it is an expression of a collective weariness with life, a loss of transcendence, a radical individualistic egoism, and a break with tradition. Those who no longer see themselves as part of a chain of generations, but only as isolated individuals, may destroy the present, but in the long run they will no longer be able to shape the future.

This text has first been published in the German language on “Corrigenda” and serializes updated elements from the book by the same author: “Auf dem Weg ins Imperium? Die Krise der Europäischen Union und der Untergang der römischen Republik. Historische Parallelen, Berlin / Munich, 2014 (Europa Verlag Berlin), 544p.”

Very good. Should fiction be fact? “Equality is no longer understood as a political and moral ideal, but as an anthropological fiction: all people are equal, always, everywhere, in everything. “